Hospice du Rhône, Rhône Grapes in America & The Rocks District

La Terre Parle (The earth speaks)

Hospice du Rhône, the annual celebration of Rhône grape varieties and producers, was scheduled for April 22-24 before it was cancelled due to the ongoing Covid-19 crisis. Two of the cancelled seminars would have highlighted vineyards in the newly established (2015) Rocks District of Milton-Freewater AVA,1 a geologically distinct sub-AVA within the larger Walla Walla Valley AVA. Let’s celebrate local terroir from the comfort of our homes by learning about Rhône grapes in America and the people that have championed them!

Cornas, Rhône

Hospice du Rhône

It started with a bottle of Viognier and a joke.2 Mat Garretson, one of the founders of Hospice du Rhône, was a red wine drinker until he popped a bottle of Domaine Georges Vernay Condrieu. He was cooking something that called for white wine, and he was about to deglaze the pan when the aroma of honeyed apricot stopped him in his tracks. This bottle of Viognier from the northern Rhône inspired him to create an appreciation society focused on the grape. He met John Alban, one of the Rhône Rangers (more on them later) and an early proponent of Viognier.3 Together, they would expand the society into a non-profit business league and international vintners’ association that meets yearly in Paso Robles. They promote producers around the country that grow and vinify Rhône varieties like Syrah, Grenache, Mourvédre, and Viognier. The Hospice du Rhône tastings and seminars are the place to rub elbows and exchange ideas with American and international Rhône royalty. Their director, Vicki Carroll, was recently named Wine Enthusiast’s Person of the Year.

Rhône Grapes in America4

Rhône varieties have been planted in the US since at least the mid-1800s. Old-vine mixed black plantings in California are usually Zinfandel-based, but they often include smaller amounts of Grenache, Mourvédre (Mataro), Carignan, Syrah, Cinsault, Counoise, and others. These grapes were typically picked together as a field blend, and it wasn’t until the 1970s that producers, inspired by the Rhône heavy imports of Kermit Lynch, began searching for single-varietal Rhône plantings.

Joseph Phelps released the first varietally labeled Syrah in 1977, and although everyone agrees that it was horrendous,5 Phelps remained committed to the variety. Gary Eberle, another Rhône fanatic, planted the first modern Syrah vineyard shortly thereafter, establishing Estrella River with vine material from Chapoutier in Hermitage by way of UC Davis.6 In the decade that followed, young winemakers like Randall Grahm, Steve Edmunds, Adam Tolmach, Bob Lindquist, and (the aforementioned) John Alban would all focus their production on Rhône grapes. By the time Grahm appeared as the “Rhône Ranger” on the April 1989 cover of Wine Spectator, the American Rhône movement was in full swing.7

Brooke Roberston, Harvest at SJR Vineyards 2019

Rotie Rocks Estate Vineyard

Rhône Grapes in Washington

While California’s historic Rhône plantings predate the commercial Washington wine industry,8 there was varietally labeled Rhône wine made in the state as early as 1969 (Grenache rosé). While cold-tender Mediterannean varieties (especially Grenache and Mourvédre) can struggle with winter damage, Syrah’s home in the Northern Rhône is more continental,9 making it ideal for Washington vineyards. Mike Sauer, owner of Red Willow Vineyard in Yakima, planted the first Washington Syrah in 1986 using budwood that originated at Joseph Phelps.10 Eight years later, the Phelps (or Espiguette) Syrah made its way to Walla Walla, migrating south to Milton-Freewater shortly thereafter. There are many beautiful local expressions of Grenache, Mourvédre, Viognier, and other Rhône grapes, but this is the story of one grape and one place.

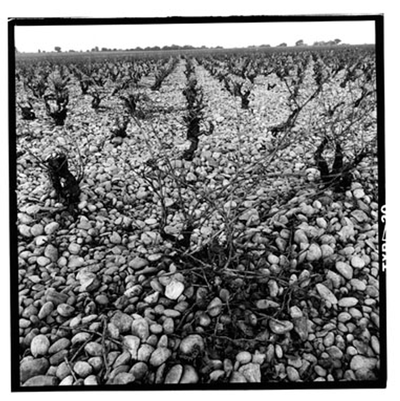

Rocks District Chateauneuf du Pape

The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater

The title of this piece comes from the cellar of Edmunds St. John. A member of the Peyraud family from Bandol, Mourvédre royalty, was tasting wine with Steve Edmunds. He came to a glass of Mourvédre, his eyes rolled back in his head, and all he could say was, “la terre parle.” Great terroir speaks, and the wines of the Rocks District speak loudly. The rocks that give it its name are alluvial cobblestones deposited by the Walla Walla river ages and ages ago. It was these cobblestones that drew a young Christophe Baron to plant Syrah in Milton-Freewater in 1997. He was reminded of the rocky terroir of famous Châteauneuf-du-Pape vineyards like La Crau. The AVA was established in 2015, covering a petite five square miles of rocky valley floor.

These free-draining, poor soils tame the inherent vigor and verve of Syrah, although the wines are anything but domesticated. The French have a term, sauvage (wild), that is frequently applied to the furry, sanguineous Syrahs of Cornas or St. Joseph. Wines from the Rocks District have sauvage in spades. They can smell like iron, or dry-aged beef, or creosote, like venison roasted on a campfire. Their texture, often buoyed by a high ph, is as soft and layered as a well-made bed, leading to a ferrous, saline[11] finish. Rocks District Syrah is a bear in a blanket, waiting for Goldilocks. The best examples can age for a decade or more, but they drink surprisingly well on release. Wine Spectator has called the Rocks District of Milton-Freewater “the most distinctive AVA in the United States.” I look forward to hearing what it has to say in the coming years.

[1] American Viticultural Area

[2] The Hospice du Beaune is arguably the most important annual wine auction in France.

[3] And other Rhone grapes. Alban’s selections of Syrah, Grenache, and others collected during his travels in France remain highly sought after.

[4] Anyone interested in a more detailed history of these grapes should find Patrick Comiskey’s American Rhone

[5] Waterlogged, virused vines struggled to ripen and the wine finished below 12% abv.

[6] The Estrella River selection remains one of the most planted Syrah clones in California.

[7] Not everyone in the Rhone Ranger camp was pleased with the French comparison. Sean Thackrey, who appears in Merriam Webster under “iconoclast”, famously complained that copying the French would stifle creativity and their Californian identity, to which Randall Grahm replied, “Sort of a coat-tails du Rhone?” See Randall’s blog for more wine geek witticism.

[8] Though many of the early home winemakers planted Cinsault (called Black Prince), one of the varieties allowed in Chateauneuf-du-Pape. There is still a planting of Cinsault in the Rocks District from 1930!!!

[9]When asked when he likes to pick, Gerard Chave answered, “Ideally before it snows.”

[10]I like to think of this wine synchronicity as an ouro-pour-os, or a wine glass drinking itself.

[11] Unbuffered potassium is a possible culprit.