Etna...Taste the Volcano

Map of Mt. Etna

Taste the Volcano

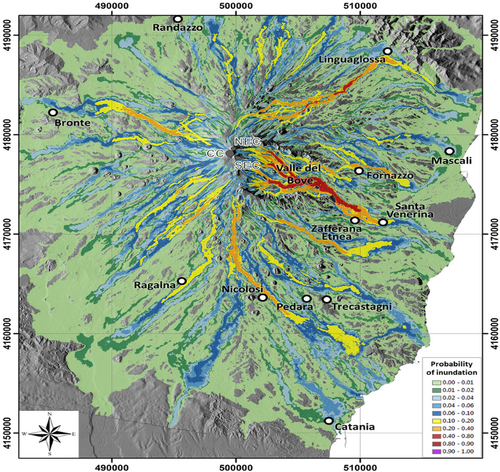

The next time you hear a local vineyard manager complaining about mildew pressure, drought, or frost, remind them that the vineyards of Mount Etna in Sicily face those same challenges, as well as the constant threat of burning ash and MOLTEN LAVA! Some years, the mountain is quiet. Other years, as in 1981, houses and vineyards are destroyed. Most terroir, from the Jurassic limestones of the, uh, Jura, to the fractured basalt of Eastern Washington, has been in place for millions of years. Etna, on the other hand, is continually remaking itself, adding layers of ash and rock with each new eruption. After each discharge, vignerons scramble to plant on the new surface. These are vineyards forged from fire and ash.

The vines of Mt. Doom, I mean Etna, cling to the side of the active volcano at elevations as high as 4,300 feet, making them some of the highest commercial vineyards in the world.1 Traditional vineyards are planted “albarello” style (little tree), meaning each vine is trained up a post.2 These old vineyards are often densely planted polycultures with olive trees, fruit trees, and other crops scattered among vines that can be as much as 240 years old. Phylloxera seems to avoid black volcanic soil,3 and the oldest vineyards remain ungrafted. Etna has produced wine since Roman times, but most of its vineyards sat abandoned until its resurgence of the last 30 years. The Benanti family founded their winery in 1988, marking the first modern investment in the region.

Etna is home to many indigenous varieties, but there are really only a couple that you need to remember. The reds are made from Nerello Mascalese (sometimes with a little Nerello Cappuccio or Alicante Bouschet thrown in for color), while the whites are typically Carricante based. Nerello Mascalese is a late ripener, often hanging well into November. Its wines are perfumed and earthy with a waft of volcanic ash, recalling blood oranges, and lapsang souchong tea. They are often compared to Nebbiolo or Pinot Noir, wines that show sous bois (undergrowth or forest floor) aromas. If good red Burgundy smells like walking through a damp forest, then Etna Rosso smells like walking through that forest a year after a fire.

Carricante, like its translucent red counterpart, couldn’t hide its volcanic origins if it tried. This neutral, savory white often grows on the eastern side of Etna in vineyards where Nerello Mascalese would struggle to ripen. The Etna Bianco DOC requires that a wine be at least 60% Carricante, and Superiore wines must be 80%. It’s a high acid grape, presenting citrus fruits of lemon or orange, but we’re here for the rocks. The best examples scream volcano with pyroclastic minerality4 like a sprinkling of smoked sea salt, which stretches the finish and leaves you looking forward to your next sip. Carricante means “loaded”, and it must be short pruned to tame its tendency to overbear. With careful viticulture, Carricante can produce profound wines that rival Italian classics like Soave, Fiano, and Verdicchio in ageability and intensity, cellaring for 10 years or more. What do the next 10 years hold for these vineyards? Only Mt. Etna knows.

[1] Check out the Valle d'Aosta for an alpine take on high elevation Italian wines.

[2] Much like echalas training in the Northern Rhone or Mosel.

[3] As in Tenerife and Santorini.

[4] Put your pitchforks away. I vote that we retire minerality except in cases where the rocks are actively trying to kill you.

“Alberello”-trained vines, photo courtesy of Louis Dressner

More “Alberello”-trained vines (and some sort of mammalian tractor), courtesy of Louis Dressner

Vincenzo Bonaccorsi of ValCerasa tending his vines A vineyard shot from Tenuta Masseria Setteporte