Our blog was created to help make the world of wine and beer easier to understand and fun to navigate. There are a million things to know in this industry, we just want to help you understand the latest news and trends from around the globe. So sit back with your favorite sip and let's go on an adventure.

Pairing Wines with Thanksgiving Sides

ROCKIN' REDS FOR THE TURKEY TABLE 6-PACK, SHOP HERE

Not-so-hot take alert - Thanksgiving is all about the sides! Every single one of us has a relative who would commit avian war crimes every holiday season, conducting thermonuclear weapons testing on white meat turkey until it shattered in your mouth. These well-intentioned relatives would sacrifice frivolous, decadent concepts like “flavor” and “texture” in favor of a desiccated Norman Rockwell shell that deflated as soon as Uncle Rob got out the electric carving knife. You and your cousins would duel with salad tongs to see who got the only edible bites of dark meat, while the rest of the family choked down slivers of breast meat. The horror…

Luckily, there were side dishes. Casseroles, mashes, stuffing, and dressing (the difference escapes me, but I haven’t brought it up since Aunt Jacky and Uncle Kevin’s tense ceasefire of ‘97), roasted veggies, and gggggrrrraaaaavvvvvvyyyyyy! Nectar of the gods, culinary panacea, restorer of succulence, keeper of the peace, and defender of the realm of Thanksgiving with the family.

There is only one hitch in a wine lover’s buffet of Thanksgiving side beneficence - pairing wine with turkey is a snap (just follow the general rules for roast chicken), but what about the sides? What, besides marshmallows, goes with sweet potatoes? “(“Drowsy” uncle voice) What even is a brussel sprout, really?” Fear not, Thanksgiving drinker, The Thief is here to help! These are some of our favorite side dish pairings with wines that are also all perfect for that roasted bird centerpiece.

Anne-Sophie Dubois Fleurie Les Cocottes 2019

Anne-Sophie Dubois is one of our favorite producers in Beaujolais. Her bright, floral Fleurie, all clean lines and pillowy carbonic texture, with oodles of raspberry and strawberry, is perfect for the ubiquitous side of mashed sweet potatoes or roasted squash. Blend up some roasted squash with coconut milk and red curry paste for a delicious, spicy curried soup that makes a great starter.

Francois Chidaine Touraine Gamay 2019

Chidaine, one of the most inspiring farmers in all of France, produces biodynamic Chenin blanc, Sauvignon blanc, and this Gamay from his no-till, carbon-sequestering vineyards in the Loire. This Gamay is spicier and denser than Dubois’s, with darker fruit and a touch of leafiness that reminds me of a Cabernet Franc from the region. Sausage and Gamay is a classic pairing, so pour this when the sausage and sage stuffing makes it to your plate.

Domaine Sebastien David Hurluberlu Cabernet Franc 2019

Sebastien David’s funky, Coke bottle Cabernet Franc is perfect for anyone who enjoys stuffing version 2.0 - cornbread stuffing. The red and green capsicum notes of Loire Cabernet Franc pair beautifully with the southwest flavors of cornbread stuffing with roasted poblano chiles. The earthy spice and herbaceous tang will also elevate butter-roasted mushrooms with thyme and garlic.

Poderi Cellario E Rosso! NV

Barbera is incredibly versatile on the table, and this bright, natural wine comes in a one Liter bottle, so you’ll have plenty to go around. Barbera’s friendly fruitiness and acidity are perfect for difficult pairings like bitter vegetables. I like to brighten the umami-laden Thanksgiving table with a bright, punchy, raw Tuscan kale salad. Just dress thinly chiffonade-ed kale with lemon juice and olive oil, leave it to marinate and tenderize for a few minutes, then toss with sharp pecorino or parmesan. Serve with pine nuts if you like, or just a second glass of Poderi Cellario Barbera. Extra credit - this wine is perfect if you’re one of those folks who has abandoned turkey altogether in favor of a standing rib roast.

Weninger Blaufrankisch Kirchholz Alte Reben 2015

When in doubt, follow the number one rule of wine and food pairing - if it grows together, serve it together. This biodynamic Blaufrankisch (also known as Lemberger) from far eastern Austria is perfect with bacon-roasted brussels sprouts, roasted beets tossed with cumin seeds, and other eastern European flavors. It is dark and spicy, with cracked black pepper and blackberry coulis that make me think pork or game (maybe wild boar?), if you’re avoiding turkey.

Francois Labet Bourgogne Rouge Vieilles Vignes 2016

Labet’s old vine bottling is an absolute steal, with pretty red fruit and classic Burgundian polish framed by sappy whole cluster tannins and turned earth, like someone in a fancy ball gown or tuxedo who also has calluses on their hands and dirt under their fingernails. The slight stemminess, combined with Burgundy’s affinity for mushrooms, makes this wine ideal for classic green bean casserole. I usually like to make my own mushroom gravy, but I will never sneer at mushroom soup or mix.

As mentioned, all of these wines are awesome with simple salt and pepper roasted turkey (consider spatchcocking it to help the white meat and dark meat cook at the same rate), or deep-fried turkey, or smoked turkey, or flamethrower scorched goose, or confit-ed wild grouse, or whatever fowl you are planning to serve. If you are still thirsty when pie is served, feel free to switch to one of our sticky dessert wines. Port or Banyuls are perfect for pumpkin pie, while Tokaij, sweet German Riesling, or Sauternes are great with orchard fruit desserts like apple pie or Bosc pears poached in white wine. Eat well, drink well, and please be safe this Thanksgiving season. Cheers!

ROCKIN' REDS FOR THE TURKEY TABLE 6-PACK, SHOP HERE

Fleurie's Gracious Host: Jean-Louis Dutraive

FLEURIE JOIE DE VIVRE DUTRAIVE 3-PACK, SHOP HERE

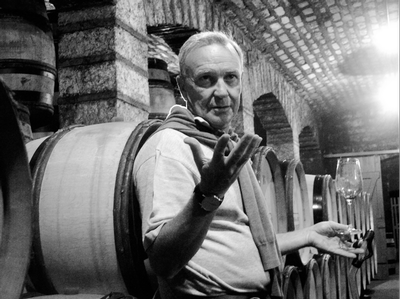

We in the wine industry have a tendency to idolize reclusive winemakers, to lionize the hermit-artists who just want to be left alone with their barrels and bottles. Jacques Reynaud, the former owner of Chateau Rayas in Chateauneuf-du-Pape, was famous for hiding when journalists and importers would come calling, going so far as to crouch into a ditch to avoid an appointment with a famous wine writer. The cellars of Coche-Dury and Domaine de la Romanee-Conti (makers of arguably the greatest white and red Burgundies, respectively) are notoriously difficult to visit. The most famous hill in the Rhone was literally a medieval knight’s hermitage!

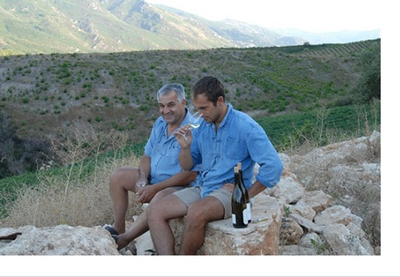

Jean-Louis Dutraive, on the other hand, is no shrinking violet. His domaine in the Beaujolais Cru of Fleurie has become a crossroads for visiting wine professionals, winemakers both local and imported and a rotating cast of interns from around the world. His devotion to casse-croute is famous (specially locally made sausages), and any visit to Dutraive’s cellar is bound to include a meal, along with enough Fleurie to float you to Lyon.

Dutraive’s family has been farming the Domaine de la Grand Cour since the early ’70s. The heart of their holding is the Clos de la Grand Cour, a walled vineyard whose vines are now more than 50 years old on average. Jean-Louis took control of the domaine in 1989, slowly fortifying his holdings to the current ~25-acre expanse. All of his estate vineyards have been farmed organically for decades (though they were only certified in 2009), and he incorporates herbal teas as well as plowing with donkeys to further lessen his environmental impact.

Domaine de la Grand Cour’s winemaking is similar to the famous Gang of Four. All of the grapes are hand-picked into small bins before they are refrigerated overnight. The cold grapes are loaded into small cement cuves the following day, covered with CO2, and left to carbonically macerate for 15-30 days. As with other natural Beaujolais producers, there is no addition of sulfur before or during fermentation, and the macerations are rarely touched at all, except for analysis. Dutraive describes his winemaking as “low intervention, high surveillance”, which is similar to other natural producers like Lapierre or Foillard.

Jean-Louis’s wines are as open and friendly as his cellar. Cool carbonic maceration leads to intensely aromatic wines with delicate, filigreed tannins that drink well on release, while also aging remarkably well. Fleurie is known as a lighter, more floral Cru than the more structured wines of Morgon or Moulin-a-Vent (some even believe, wrongly, that this florality is where the village got its name. It is actually named for a Roman general, Floriacum), and Dutraive’s wines take this luminosity to a different level. His Fleuries are often among the appellation’s lightest in color, but they are also some of the most intense, with flower-shop aromas of wet rose petal, violet, and agua de jamaica, and a palate that bursts with fresh red fruits like pomegranate, sour cherry, and wild strawberry. If I had one critique, it would be that they are almost too friendly, too easy to drink. Just what you would expect from one of the wine world’s most gracious hosts.

FLEURIE JOIE DE VIVRE DUTRAIVE 3-PACK, SHOP HERE

Lapierre: 100% Grape Juice

100% Grape Juice

“Our ideal is to make wine from 100% grape juice.” - Marcel Lapierre

BEAUJOLAIS GANG OF FOUR PACKAGE DEAL, SHOP HERE

It’s a simple idea: glossy, fragrant wines made from old, low-yielding, organically farmed Gamay vines. Unfined, unchaptalised, unfiltered, with only a sprinkling of sulphur at bottling, if at all. Wine produced solely from grape juice should not be a controversial idea. When you learn the full range of enological powders, potions, and poultices, though, you realize that we take for granted the industrial processes and additives that bring us the majority of the world’s wines.

The systemic use of chemical herbicides and pesticides in the vineyard and additives in the winery began after World War II and accelerated during the ’70s and ’80s. This is the wine world that Marcel Lapierre entered when he took over his familial domaine in the 1970’s. The recipe for Beaujolais was simple then: push yields as high as the Appellation allowed, pick before full ripeness to avoid inclement weather, chaptalise heavily, ferment quickly using selected yeasts, and shovel as much Nouveau into the market as it would take. Lapierre worked this way for several years, growing more and more frustrated with his results. It was not until 1981, when Marcel met Jules Chauvet, that Lapierre Morgon was truly born.

Look at the back of a wine label. There will be a warning about alcohol and sulfites, and very little else. Unlike other food products, wine labels are not required to list ingredients. Chauvet, a chemist, and brilliant taster, convinced Lapierre to set aside his herbicides, yeasts, and table sugar, relying instead on the plow and the microscope. This style of winemaking is sometimes called a la ancienne, or ‘the old way”, and it was said that Lapierre rediscovered the old taste of Morgon. His neighbors took note, and soon producers like Jean Foillard, Guy Breton, and Jean Paul Thévenet (sometimes known as the Gang of Four) began to work in a similar fashion. It was decades before Cru Beaujolais would receive international recognition, but the foundation was laid in Marcel Lapierre’s cellar. To this day, the domaine’s back labels still indicate whether the cuvee was sulfured (“S”) or unsulfured (the highly sought after, infrequently imported “N” bottles).

As I mentioned, it starts with intense, meticulously farmed grapes from some of Morgon’s finest climats (such as Cote du Py). Whole grape clusters are transported to the heavily-muraled winery, where they may chill overnight in a refrigerated truck. They’re then loaded into large wooden fermenters for a long, unsulfured carbonic maceration. Carbonic maceration is a complicated anaerobic enzymatic process; all you really need to know is that this is what gives Cru Beaujolais its beautiful aromatics and silky texture. After 2-4 weeks, the grape clusters are raked out and pressed, producing a low alcohol (~4%) juice called “paradis”. This juice is transferred to barrel or foudre, where it completes alcoholic and secondary fermentation under constant microscopic observation.

These days, it is Marcel Lapierre’s children forking grape clusters and running the microscope. Marcel passed away during the harvest of 2010. His children continue to produce Morgons in the house style that he debuted 40 years ago, and the Gang of Four continues to inspire natural winemakers the world over. Lapierre Morgon is a melange of bright berry intensity, allspice bite, and granitic nervosity, like skipping a wet stone across a raspberry juice pond in mid-fall; a true benchmark in the world of grape juice.

“Nobody’s wines taste like Marcel Lapierre’s. He is the source of a whole new school of winemaking, turning the hands of time back to wine the way Mother Nature envisioned it. Tasting it can change the way you taste wine.”

- Kermit Lynch, American importer for Marcel Lapierre and the Gang of Four

BEAUJOLAIS GANG OF FOUR PACKAGE DEAL, SHOP HERE

Corsica's Siren Song

Familiar grapes with unfamiliar names. Autochthonous varieties with even more difficult names. Is this an alpine, mountainous paradise? Is it a beach bum’s island delight? French? Italian? Something else all its own? Corsica is like one of those scrambled optical illusions that resolves itself into a familiar image if you stare at it long enough. I know what to expect from a Chianti or Brunello, but a Niellucciu? Inform me that it’s just a local clone of Sangiovese though, and the picture comes into focus. Yeah, this herby, red-fruited, leathery wine is exactly what I would expect from someone growing Sangiovese on a windswept granite spire in the middle of the Mediterranean.

“I first set foot on the island in 1980. I remember looking down from the airplane window seeing alpine forest and lakes and thinking, uh oh, I got on the wrong plane. Then suddenly I was looking down into the beautiful waters of the Mediterranean. Corsica is a small, impossibly tall island, the tail of the Alp chain rising out of the blue sea.” - Kermit Lynch

First, some orientation. If you sailed a ship directly east from the Italian coast near Rome, you would run smack dab into Corsica. It sits just to the north of Sardinia, and southeast of Marseille and Monaco. The ancient Greeks called it The Land of Sirens, and the cliffs of southern Corsica surely smashed more than their share of boats during antiquity. The island is battered by the famous mistral winds of southern France and the scirocco from northern Africa. Between the winds and poor soils of granite or limestone, Corsica is about as inhospitable as a Mediterranean island paradise gets, a major boon for the local wine industry. As we know, grapes love a challenge.

Much of Corsica’s history is Italian. It was ruled by the Republic of Genoa from the 13th century until the 18th, when it was unceremoniously sold to the French to pay off debts. While Emperor Napoleon was Corsican, most modern-day Corsicans have a strong independent streak. All of the island’s signs are written in native Corsican as well as French (often with the French translation scratched out), and nationalist identity has led to conflict in the past.

This French-Italian blend (with a healthy balance of Corsican distinctiveness) is reflected in the local grape varieties.

● Vermentinu - the local name for Vermentino. Also known as Pigato in Liguria or Rolle in the south of France, this white varietal produces some of Corsica’s finest wines. Expect lemony citrus, white flowers, resinous bite, and a distinct saltiness.

● Bianco Gentile - An aromatic, dense white, this variety almost went extinct before Antoine Arena propagated cuttings from the last remaining vineyard. Honey, chamomile, and chalk are classic notes.

● Niellucciu - meaning “little black”, this local clone of Sangiovese made its way to Corsica from Italy during the Middle Ages. As previously mentioned, you’ll find red cherry fruit, leather, and a dusty herbaceousness similar to the garrigue of the southern Rhone and Provence, known locally as maquis (wild myrtle, fennel, immortelle, and juniper bush).

● Sciaccarello - another local red variety that is known for its peppery spice and intense herbaceousness. Commonly used in rose production, though more quality producers are vinifying it as red wine.

Corsica has a long viticultural history (I have read that it once had more acres of vineyard planted than Bordeaux), and recently the quality and availability of the wines has exploded. The Arena family, currently our favorite producers on the island, has been instrumental in the advancement of local wine production, while staying firmly rooted in Corsica’s layered history.

Antoine Arena is the godfather of modern Corsica. His organically farmed wines, especially his whites, show precision, density, and a tremendous capacity for aging. As he has stepped away from the business, he has ceded more and more of his vineyards to the next generation, splitting his domaine between his three heirs. Antoine-Marie Arena, fresh from several winemaking apprenticeships on the french mainland, has inherited several of his father’s best plots of Vermentinu, Niellucciu, and Bianco Gentile. His viticulture and winemaking mirrors his father’s: organic vineyards (including some biodynamics) with plowed soils and natural manure, long native ferments, and bottling with minimal sulfur or filtration. These wines are fresh, sappy, and structured, perfect for local delicacies like fresh goat cheese, wild boar, or lamb. I wouldn’t be surprised if they called you, time and again, back to Corsica.

ISLAND WINE TRIO, SHOP HERE

Antoine-Marie Arena Patrimonio Hauts de Carco 2018

- Corsica, France

- Appellation Patrimonio Protegee

- 100% Vermentinu (local name for Vermentino)

- Limestone soil

- Certified organic

- Native yeast fermentation

- Primary and secondary fermentation in stainless steel tank

- Aged 12 months in 300L barrels

- Valencia orange, green apple, salt spray

Jansz Tasmania Premium Cuvee Brut NV

- Tasmania, Australia

- 60% Chardonnay, 40% Pinot noir

- Fermented and aged in both stainless steel and hogshead oak barrels

- 100% malolactic fermentation

- Bottle aged for 2 years on lees

- 8.6 g/l residual

- 93 points WE, 90 points WS, 90 points JS

- Lime, apple, lemon tart

Colosi Nero d’Avola 2018

- Messina, Sicily

- 100% Nero d’Avola

- Calcareous and clay soils

- Fermented in stainless steel

- Aged 6 months in stainless, preserving freshness

- Blackberry, black pepper, black olive