Our blog was created to help make the world of wine and beer easier to understand and fun to navigate. There are a million things to know in this industry, we just want to help you understand the latest news and trends from around the globe. So sit back with your favorite sip and let's go on an adventure.

You've Been Drinking Volcano Wines This Whole Time...

Every time Mount Etna erupts, a new terroir is born. When the dust settles and the vignerons return to the slopes, they discover a viticultural landscape remade by ash and molten rock. How fricking metal is that (eat your heart of Blood of Gods)?

From the dizzyingly braided trenzado vines of Tenerife in the Canary Islands to the Gamay-covered extinct volcanos of Auvergne and Beaujolais, from the bell rung Chardonnays of the Willamette Valley’s Jory soils to the fractured basalt crackling beneath Cabernet vines in our own Valley, volcanic wines make up a disproportionate percentage of the wines of the moment (apologies to Kermit Lynch, I know he’s been trying to make Corsica a thing for like decades). What self respecting wine nerd wouldn’t want to try a light bodied red wine growing out of the side of an exploding mountain?

When I think about volcanoes and their wines, I think about tension. Tension is the difference between the slow, consistent eruptions of Hawaiian shield volcanoes versus the abrupt explosion of stratovolcanoes like Mount St. Helens. Tension is the difference between a wine that makes you go “meh” and a wine that has you pouring a second glass before you’ve finished your first. Volcanic wines (Usually. Generally. Typically. Blah blah blah...) are wines of tension. Wiry without being bony or lean, dense but not lumbering, volcanic wines are popular because they are exciting. They come from exciting locations, are grown in unusual ways with unique grape varieties, and continue to intrigue when they make it into your glass.

The relative isolation of these volcanic wine regions (many of them are islands, after all) means that they are often very distinctive viticulturally. In Santorini, own-rooted Assyrtiko vines have been slowly woven into tightly wound baskets over the course of centuries. The baskets form a dainty protective layer, shielding the grape bunches from the crushing Mediterranean heat and blowing winds.

Similarly, the vineyards of Tenerife have historically been trained into long, creeping, xenomorphic cords. Like in Santorini, these vines are very, very old (up to 200-250 years old) and own-rooted, predating the introduction of phylloxera to Europe. Phylloxera seems to struggle in volcanic soil, and many of the vines in these regions are planted on their own roots (their isolation doesn’t hurt either). The grape varieties follow a familiar Spanish colonial pattern, with Palomino and Mission (known here as Listan Bianco and Listan Prieto, respectively) taking center stage alongside the autochthonous red variety Listan Nego. The whites are sea spray and almond, the reds are smoky forest berries, and you should devour them both with as many salty foods as you can handle.

.

.

The aforementioned vines of Mount Etna are trained in the traditional alberello style, similar to a Rhone valley goblet but taller. Apologies in advance for the broken record: black volcanic soils, own-rooted vines planted to unique varieties, transparency, ageability, smoke, tension. The reds, typically Nerello Mascalese with a dollop of Nerello Cappuccio, drink like Aphrodite mixed all the leftover bottles after one of Hephaestus’s famous “Burgundy and Barolo Bashes”. The Carricante-based whites are citrus laden, saline, taut, and crisp (you ever make preserved lemons? Did you lick your fingers?), and they age spectacularly. We love these wines so much that we made an entire section for them. The entry level wines represent some of the most consistent values in Italy, and the high end stands toe to toe with the grandest cellar selections in the world.

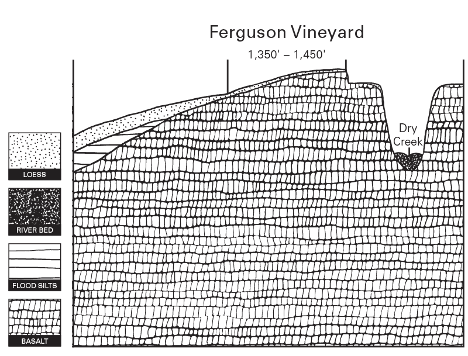

Volcanic wines are not restricted to far flung islands with twisted vineyards and difficult to pronounce grapes. The wines of Walla Walla are also volcanic! Our basalt bedrock, from the rolled cobblestones of the Rocks Distict to the fractured basalt of Sevein and the North Fork, is part of the Columbia River Basalt Group, the result of millions of years of lava flows. You’ve been drinking volcanic wines this whole time, whether you knew it or not. I’m pretty sure that makes you a wine nerd. Welcome in! Take a seat. Pour yourself a glass or two. You look tense.

Thoughts on the Loire Valley

Chenin Blanc

Harvest at Domaine du Viking

Harvest at Domaine du Viking

Silex flint soils at Domaine du Viking

Silex flint soils at Domaine du Viking

Plowing at Huet

Plowing at Huet

Quick, name the most versatile wine grape you can think of. A grape that conjures operatic roars from traditionalists, yet also makes the hipsters quit slouching and sit up in their 1chairs. A grape whose dry wines offer depth and lift in equal measures, like lightning striking the ocean. Whose sweet wines can last for generations 2. A grape that makes brilliant sparkling wines with pedigree, age-ability, and vintage statements. A grape that was planted extensively in eastern Washington during the early years of vineyard establishment, championed by Walter Clore. This grape, of course, is…

Shouts from the assembled digital crowd - “Riesling!!!”

Chenin Blanc!

Ok, you’re right, I forgot about Riesling. Fine, Chenin Blanc is one of the most versatile wine grapes. Would you like wines of “punk rock violence, yet of Bach-like logic and profoundness”, to quote the estimable Becky Wasserman? Chenin can do that. Do you need a vine you can crop at 10+ tons/acre while maintaining acidity? Chenin can do that too, Mr. California Chablis. The Dutch brought Chenin Blanc to South Africa in the 17th century to ward off scurvy and boredom, and it is still the most planted variety in that country. The Central Valley of California crushed 300,000! 3tons of Chenin in the late 80’s. From stubby bush vines in the deserts of the Swartland, to tight, temperate rows in the Willamette Valley, Chenin Blanc can go anywhere and be anything.

Though it travels well, the Loire Valley is Chenin’s home. There are references to it as far back as the 9th century, which, I am told, was a very long time ago. If the Loire is its home, then the village of Vouvray is Chenin’s bedroom, complete with Ramones posters and Dead Kennedys stickers. The ultimate punk rock empress of wine, one Jancis m-fing Robinson MW, wrote in her mandatory tome The Decline of Western Civilization 4, “Vouvray is Chenin Blanc, and to a certain extent, Chenin Blanc is Vouvray.” Vouvray contains all of Chenin’s multitudes 5 (dry, off-dry, sweet, very sweet, sparkling, red 6), as well as many of its greatest individual expressions. The biodynamic wines of Domaine Huet are probably the most famous in Vouvray. They cover the full stylistic range, and their sweet wines are especially well known for their capacity to age. Their vineyards, planted on the soft local limestone known as tuffeau and harvested in multiple passes (or tries), produce what many would consider the archetypical moelleux (soft, aka sweet) Vouvray.

The Chenin vines of Domaine du Viking dig through hard silex flint that is only found in the very north of the appellation. There, Francoise and Lionel Gauthier vinify their Vouvray in the sec tendre style (tender dry), similar to a halbtrocken Riesling. There is some residual sugar here, but it is well balanced by Chenin’s brilliant acidity. The Domaine’s importer has this to say of Lionel Gauthier’s winemaking prowess - “It can be said without any equivocation that Lionel Gauthier can eat more sweetbreads than you can.” A glowing endorsement if I ever heard one.

Chenin’s versatility lies with that acidity. If picked underripe, it can be bony and puckeringly tart7. It maintains this acidity late into the season while adding heft and curves to its bones, draping itself in waxy pome fruit while never losing that structural framing. The best Chenins are like an orchard next to an apiary, or like you thought a quince might taste before you’d actually tasted one. Botrytis might bring ginger and honey to the party, and the low so2 crowd might bring mixed nuts, but Chenin will bring acidity with it wherever it goes.

Notes From the Author

[1] Ok, you caught me, “our.”

[2] The 1947 Huet was named one of the 100 greatest wines ever by Decanter magazine.

[3] That’s 40,000 more tons than all of the grapes crushed in Washington in 2018, our largest harvest ever.

[4] Or was it The Oxford Companion to Wine?

[5] I believe Walt Whitman wrote I Sing the Body Electric while sipping a particularly glowing Vouvray

[6] Jk, although the rare red grape Pineau d’Aunis is sometimes known as Chenin Noir

[7] “One of the nastiest wines possible” according to Oz Clarke.

Sauvignon Blanc

Monts Damnes

Monts Damnes Photo Courtesy of Rare Wines

Photo Courtesy of Rare Wines

Monts Damnes

Monts Damnes

This is the story of a vineyard in Sancerre that has been forgotten in plain sight. A vineyard that checks all of the great terroir boxes: originally planted in the 10th century by very thirsty Benedictine monks, precipitously steep south-facing hillside that wouldn't look out of place in Cote Rotie or the Mosel, bright white limestone soils1studded with freakin’ fossilized sea shells2, old vines tended by hand out of necessity on said black-diamond steep hill, with a name like a Norwegian metal band, in the best village in one of the best regions for white wine in all of France. Somehow, wines from the vineyard of Les Monts Damnes, translated literally to the Damned Mountain, the greatest terroir in Chavignol, are criminally undervalued. For now.

Outside of the wines from a couple of visionaries like Didier Dagueneau and Edmond Vatan3, very few wines from Sancerre are considered vin de garde. Most Sancerre is fresh and immediate, as easy to slurp as it is to pronounce, and we love it unabashedly. The wines from Monts Damnes are different animals altogether. It starts, as always, with the vineyard. As mentioned, the slopes of Monts Damnes are so steep that some producers provide cushions for their pickers to sit on while they slide down the hill. It’s a hill made for skiing4 rather than planting, and many vignerons allow grass cover crops to grow between the vines to prevent erosion. The southern aspect and extreme pitch maximize sun exposure for the vines, allowing for greater ripeness than in the flats of Touraine.

Producers use more wood for fermenting and aging Monts Damnes than in the rest of Sancerre. Young Matthew Delaporte of Domaine Delaporte uses large format5 used oak barrels on his Monts Damnes. His family has operated in Chavignol for more than 300 years, but the 31-year-old winemaker refuses to rest on his laurels, converting his vineyards to organic certification6, allowing full malolactic fermentation, and extending the lees aging of his finest cuvees up to 12 months. His tweaked vinification, which mirrors the efforts of regional stalwarts like the Cotat cousins Francois and Pascal, embraces the substance and heft that this site provides.

Accordingly, the wines from Mont Damnes are richer than your typical gooseberry and nettle Sancerre, with yellow fruit, ripe citrus, and a resinous density that would not seem out of place in good white Burgundy. This is the sort of lazy comparison that normally drives me crazy, a shorthand way of saying that this white wine is delicious and complex now and will remain delicious and complex for several more years, but I just can’t shake it. And maybe I shouldn’t. Chavignol is closer to Chablis than it is to Nantes. The soils are the same, clay and limestone marl over an ancient seabed. Most importantly, the wines of Monts Damnes, like the wines of Les Clos, taste more of the place they are from than the grape they are made of. Les Clos doesn’t really taste like Chardonnay, it tastes like Les Clos. Monts Damnes doesn’t taste like Sauvignon Blanc. It might not even taste to you like Sancerre. More than anything, it tastes like the Damned Mountain.

Notes From the Author

[1] Terres blanches, the same soils as Chablis, which is less than 75 miles away.

[2] That everyone says you totally can’t taste, but the itty bitty shells are right there, and it’s so rocky, and naaah naah naah, I can’t hear you, minerality, minerality, minerality! Ok, fine, it tastes salty. Happy?

[3] Both of whom source their Sancerres from Monts Damnes

[4] Imagine slaloming among meter by meter plantings of old vine Sauv Blanc!

[5] 600l demi-muids

[6] “We have also stopped feeding the vines like at McDonalds.” - Matthew Delaporte

Muscadet (Melon de Bourgogne)

Photo Courtesy of Weygandt-Metzler

Photo Courtesy of Weygandt-Metzler

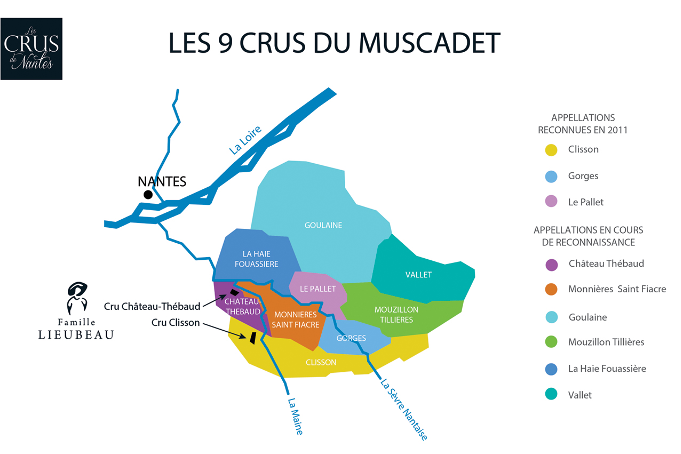

Muscadet, for better or worse, has been defined by what it is not. Not heavy, not oaky or buttery, not overly fruity, certainly not expensive. A neutral, rather than aromatic, white. A wine so transparent that it is best known for the turbid solids that it ages beside, the pillowy spent yeast cells of sur lie aging that are cast aside at bottling. Muscadet can be ephemeral if it is treated dismissively, seeming to exist only in the spaces between oysters. Its transparency, though, is also its greatest strength, enhancing and exaggerating the regional differences among Muscadet’s 9 newly established crus like a terroir-magnifying lens.

Muscadet only has one grape - Melon B, formerly Melon de Bourgogne. This lattter name was confusing for several reasons1, not the least of which being that Melon is not grown in Burgundy, at least not anymore. Melon’s tumultuous relationship with, and eventual banishment from, Burgundy mirrors another of our favorite grapes: Gamay. You could say that they both got Beauned. Gamay was famously cast out of Burgundy by Phillipe the Bold in 13952, while Melon lasted until the 18th century before being evicted because of overproduction3. Melon and Gamay didn’t just get kicked out of the same childhood home; in fact, they’re siblings! Melon, Gamay, Chardonnay, Aligoté, and countless other varieties resulted from crosses between the aristocratic Pinot4 and the nearly extinct Gouais Blanc, which was a grape of the peasantry.

While Gamay was able to find a new home just to the south of the Cote d’Or, Melon landed 600 km west, as if Burgundy tried to throw it into the Atlantic Ocean and came up just short. Here, in one of France’s most marginal climates, Melon’s productivity and hardiness were welcomed by a local wine industry rocked by winter kill. It was here, around the city of Nantes on the coast of Brittany, that Melon met “la mer”.

Wines grown near the ocean, from Ligurian Vermentino to western Sta. Rita Hills Pinot Noir5, often taste salty, and Muscadet is no different. If oysters remind me of eating the ocean, then Muscadet is like drinking it6. When young, its nerviness makes it “the quintessential springtime wine,” according to Richard Hemming MW, a wine that pairs as well with delicate spring produce as it does with Cthulhu pulpo. Save some in your cellar and you will be rewarded with one of the great wine transformations. Aged Muscadet maintains its transparency and vitality while adding a warm sepia lens. Its briny origins and maritime structure remain, though the ocean grows as honeyed and round as if you spun cotton candy from seawater. Muscadet vigneron Jo Landron describes it as, “sugared, but with no sugar.” I can’t help but taste Burgundy by the sea.

Notes From the Author

[1] And has led me down some youtube rabbit holes that started in Muscadet vineyards and ended in a Dijonaise backyard looking at canteloupe.

[2] His description of a “very great and horrible harshness” makes me wish I could pour him a silky, pillowy glass of Lapierre Morgon.

[3] The same complaint levied at Gamay.

[4] Either Noir, Gris, or Blanc, which are genetic variations of the same grape rather than distinct varieties. I’m not an ampelographer, I don’t make the rules.

[5] See also: Santorini, Corsica, Tenerife, Cassis, the west Sonoma Coast, Chile’s Casablanca Valley, parts of Rias Baixas and western Galicia, Madeira, etc.

[6] Do not attempt to drink the ocean.

Devium & Delmas - Walla Walla Curator Club

In this inaugural shipment of the Curator Club, we have chosen to feature two exceptionally dedicated, energetic producers with tons of promise on the horizon: Delmas and Devium.

The wines of Delmas first came to my attention 8 years ago. Steve and Mary Robertson founded SJR Vineyard in 2007 on 10 acres “in the rocks” and, subsequently, created their flagship Syrah. Steve was at the forefront of the movement to create an AVA within Walla Walla solely defined by the characteristics of its terroir, and the first of its kind to cross state boundaries. The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater AVA was granted final TTB approval in 2015. The SJR Vineyard sits firmly on the western boundary of the AVA and Steve remains a vocal advocate for the region throughout the wine industry. Brooke Robertson, Mary and Steve’s daughter, heads up viticultural operations and plans to take the helm as head winemaker in the next five years. In the meantime, “Dad and I tag-team the winemaking protocol” according to Brooke. Billo Naravane of Rasa Vineyards has been the consulting winemaker throughout the project and remains close. On the horizon for Delmas? An estate Viognier and Grenache. We can’t wait.

Devium Wines is the passion project of the exceptionally talented Keith Johnson. A graduate of the Enology Program at the WWCC in 2011 (a year before Brooke Robertson), Keith has quickly proven himself to be one of the rising stars of the Walla Walla wine industry, though he’s so modest you would hardly know it. Spending time with Keith in the cellar talking about winemaking might just be one of my favorite things to do while out on a winery visit in Walla Walla. When not acting as Production Winemaker for Sleight of Hand Cellars, he devotes his time to producing his focused and inspired low-intervention wines. In fact, the reason Devium exists at all is due to the pure chance of the senses. While on a visit to French Creek Vineyard for Sleight of Hand’s old vine Chardonnay back in 2011, Keith was immediately impressed by the vineyard and vineyard manager, Damon Lalonde. Keith picked the French Creek Mourvédre’s first fruit in 2015 after an epiphany smelling the Syrah from the same site and the impetus to start the Devium project was created. Keith told me, “It’s ultimately about the vineyard, not about me.”

Delmas Producer Profile

Family owned and operated, Delmas is the realization of the Steve & Mary Robertson's dream, 35+ years strong, to honor a distinctive place, a distinctive taste. Born of unique geology found within The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater, as well as the climatic eccentricities of the Walla Walla Valley, Delmas is dedicated to producing exceptional wines of enduring value. Elegance is preferred to power and exoticism at Delmas; restraint, nuance, and those impossible-to-define, (pleasurable), qualities that elevate all great wines. Brooke Robertson accentuates the importance of the SJR Vineyard to her family’s vision: “The most important part of what we do is the family factor and our estate vineyard.”

Devium Producer Profile

Keith Johnson doesn’t like points given to wines and avoids it whenever possible. He’s confident in his wines’ pedigree and he should be – they’re deeply thoughtful and personal. Founded in 2015, Devium is his wild brain-child, devoted to creating something unique in the Walla Walla Valley, a commitment to minimalist winemaking, early picking and special vineyards. He doesn’t do blending trials for these wines either, believing that his wines should speak to “a moment in time and a specific terroir” that blending might obscure. It is about tradition and history, spontaneous fermentations and foot stomping. Keith Johnson is a purist and expresses his devotion to his craft with the utmost care in the production of these beautiful wines.

Faith and Beer - A Monk's Tale - A World of Beer

If you are a beer lover, and I am guessing that you are based on the fact that you are reading this blog post, you would be remiss not to understand the history of faith and beer. For over 1,500 years, monks around the world have used their faith and dedicated their lives to the perfection of the beer-making process. So, the next time you run into a monk (never thought I could say that), thank them for helping make craft beer what it is today.

As you study monks and brewing, you will quickly figure out that there are hundreds of monasteries around Europe that all have an incredible history and create amazing beer. However, we need to keep some focus so we will look at the most famous in Germany and the Trappists. To understand their history, we will start the story in the 6th Century and learn about Saint Benedict of Nursia and his writings that roughly translate as The Rule. These writings essentially built the first template for monastic life and imparted the wisdom of the spiritual and the administrative. At the core was the golden rule of Ora et Labora – pray and work. Each monk dedicated themselves to eight hours of prayer, eight hours of sleep, and eight hours of manual work, sacred reading, or works of charity. Augmenting this rule, was another rule that monks and the monastery must exist without outside money and through the work of the monks’ own hands through the production of goods and services built a framework for faith to perfect beer and other goods such as cheese and honey.

Now that we know where the faith and precision of the monks come from, let’s look at the history of the German monks who are among the oldest continuous brewers in the world. Today, Weltenburg Abby and Weihenstephan Abbey both claim to be the oldest continuous operating breweries in the world starting somewhere around 1040. Records aside, this has given these monks almost 1,000 years of brewing history to create some of the most revered beers not only in Germany but in the world. Each Abbey, as with most breweries in Germany, follows very strict purity rules set out in law in 1516. These principals allow for only the use of malted barley, hops, water, and yeast (wheat was added after an uprising years later). The rules make German beer narrow in variety but utterly perfect in execution.

If Germany has the history, the Trappists have the notoriety when it comes to monks making beer. The name Trappist comes from the Cistercian monastery in La Trappe, France (not where the beer La Trappe is made). In 1664, these particular monks thought that too many of their fellow monks were becoming too liberal. They introduced new, more rigorous rules, to live by and the Trappist movement was born. To carry out the financing of their strict monasteries and to expand their practices, breweries began to appear around the middle ages in Europe. Today these original Trappist breweries are world renowned for the focus on constantly perfecting the brewing process and keeping exact records.

In 1997, eight of the original Trappist abbeys came together to protect the Trappist name and the highest quality that comes from their strict production process. They created the International Trappist Association and the private logo that is assigned to any goods (cheese, honey, beer, wine, etc.) that are produced with respect to the precise production criteria. These criteria include: The product must be produced inside the walls of a Trappist monastery either by the monks themselves or with supervision, the goods are produced as secondary importance that places primary value on the monastic way of life, and finally the goods are not intended to be a profit-making venture.

Trousseau - The Artful Dodger

Trousseau is somewhat of a mystery to many wine drinkers. Indigenous to the Jura region of France, in the town of Montigny-les-Arsures, the dark-skinned grape varietal has quite the history in Europe and is known to have been cultivated for at least 200 years under a variety of names. Curiously, until recently it has most widely been known in Portugal as Bastardo where it is made into dry red table wines as well as their most famous exports, Porto and Madeira. In Spain, it can be found under other names, Merenzao and Verdejo Negro, where it is used both alone and in red blends.

The most compelling Trousseau are those that can be coaxed into a subtle and balanced expression of tart red fruit, minerality and mossy earth. Trousseau can easily become a high-octane wine, due to the naturally abundant sugars in the grape varietal. Due to this, it can be considered fully ripe and ready to pick when at a lower sugar level than other varietals, thus producing a wine that is higher in acid with less alcohol.

I first discovered Trousseau while “palate trouncing” through the wines of the Jura in my first years in the restaurant world. I was instantly taken by these unusual and rustic wines, at times confused by their strangeness and curious as to what made them so much different than the polished New and Old-World wines to which I’d become so accustomed. The initial rawness and brutality impressed but intimidated me. I was confused but not put off. As I began to dig deeper into the world of Jura wine, I discovered there existed a subtlety and odd grace to these wines that I had never had the opportunity of tasting. Odd grace – like an elephant on ice skates.

Let’s not beat around the bush: I have fallen for Trousseau. I am drawn to varietals with strange minerality and evocative dark forest matter, bright and light fruit piercing through the undergrowth to create a truly compelling wine. It can take on notes of light and bright sour cherries, ripe red fruit and expiring green matter or, depending on vinification technique, become a pungent, alcohol-driven, red fruit beast in need of a good chill. It is the forgotten street poet of grapes – full of nuance, easily irritable (thus “Bastardo”), and waiting for recognition of its subtle, easily-overlooked beauty.

New World winemakers are clearly catching on to the appeal of the varietal and Trousseau plantings are popping up with established producers’ names attached throughout the West Coast of the U.S., notably in regions where Pinot Noir, Gamay, and other Burgundian varietals have shown a success.

For the wine drinker who appreciates Pinot Noir and Gamay, these wines should easily appeal. This is food wine: gracefully footed with delightful acid and bright, pungent fruit expression, offering excellent pairing opportunities.

Pair Trousseau with: Game birds, smoked pork, berry reduction sauces, paté, or hard cow’s milk cheese (Morbier, e.g.).

“Bring in the bottled lightning, a clean tumbler, and a corkscrew.” - Dickens