Our blog was created to help make the world of wine and beer easier to understand and fun to navigate. There are a million things to know in this industry, we just want to help you understand the latest news and trends from around the globe. So sit back with your favorite sip and let's go on an adventure.

Riesling Rocks!

“Sometimes I think that every mouthful of wine that is not Riesling is wasted.” - Joseph Jamek, to his importer.

My favorite piece of wine-based media is an old grainy video from the mid 90s.1 In it, Jancis Robinson MW sits at a restaurant, drinking a bottle of Riesling. She says that, for her, Riesling produces the greatest white wines in the world. The camera pans out, and you see that she is drinking a bottle of JJ Prum Wehlener Sonnenhur Auslese from 1949. It pans out again, and a helicopter shot reveals that Jancis is drinking her nearly 50 year old bottle of wine on the top of a castle overlooking the Mosel river. A dramatic guitar solo plays, I swoon, and the Mosel flows on.

My favorite quote about Riesling also comes from Jancis. She says, in a wonderfully snide attempt to explain this noble grape’s doldrums, that, “The problem with Riesling is that, unlike Chardonnay and Pinot Grigio, it has a very powerful flavor.” Great Riesling has heft and lift in equal measure, a lithe Fantasia hippopotamus dancing ballet on your tongue. Between Paul Grieco’s Summer of Riesling and Jancis Robinson’s tireless evangelism, you probably don’t need another wine geek haranguing you to drink more Riesling. Instead, let’s take a tour of some of Riesling’s haunts. It’s nice to get out of the house.

[1]Jancis Robinson's Wine Course (1995) Episode 6: Riesling https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dtj9haNM9XY

German Vineyards "Burgundian" Riesling at Von Winning

Germany

Germany is Riesling’s home, and it produces many of the variety’s best wines. German Rieslings have been classified using the pradikat system since the 1970’s, which organizes wines based on the ripeness of the grapes during harvest.2 Germany, especially the Mosel, is at the northern edge of Riesling’s ability to ripen fully, so it is no surprise that its finest vineyards are steep, southern facing slopes that bask in the sun. Before the advent of temperature control and selected yeasts, fermentations would continue until they stopped naturally, leaving a modicum of sweetness balanced by the region’s brilliant acidity. These halbtrocken (or feinherb) wines were the style that popularized German wines throughout the world in the 18th and 19th century, though they have been supplanted in recent history by the late-harvest wines of the pradikat system, and more recently by the powerful, dry Grosse Gewachs.3

Riesling is an incredible conveyor of terroir, so its flavors and aromas vary greatly depending on the vineyard or region it is grown in. Earlier harvested Kabinett or Feinherb wines are often floral, with swaths of honeysuckle and lemon curd. Riper regions like the Pfalz provide more tropical fruits like pineapple, and the botrytized late harvest wines often smell of candied ginger or saffron.

[2] Kabinett, Spatlese, Auslese, Beerenauslese, Trockenbeerenauslese, in ascending order of ripeness

[3] “Great growths”

Alsatian Vineyards Samuel Tottoli in the Kuentz-Bas vineyards

Alsace

Just across the French border lies Alsace. While it currently resides within France, Alsace has changed hands several times in the last century or so, swapping back and forth between the Germans and French. As such, Alsace grows Germanic varieties like Riesling and Gewurztraminer, while also growing classically French varieties like Pinot Blanc. The incredibly diverse vineyards of Alsace4 have been organized into a series of crus much like Burgundy, though the Grand Cru wines must be made from either Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Gris, or Muscat.5

Alsace is warmer than most of Germany, and their Rieslings are sunny. They carry phenolic heft and dry extract that pairs well with the rich, often pork-based dishes of the region. Alsatian Riesling will have notes of ripe, golden citrus paired with a deep, mouthwatering minerality and a spicy finish.

[4] It has been said that Alsace has as much geologic diversity as the rest of France combined.

[5] With one exception: Sylvaner may be labeled Grand Cru if it comes from the Zotzenberg vineyard.

Clare Valley Vineyards

Clare Valley

Until recently, Australia was the second largest producer of Riesling in the world after Germany. The grape has been down under since the mid 1800s, and it quickly found a welcoming home in the Clare Valley of South Australia. The Clare Valley is north of the warm Barossa Valley of Shiraz fame, and it has a more temperate climate. Cold nights allow Riesling to maintain its signature acidity during long hang times, and marginal slate soils (much like the Mosel) elicit stone rampart structure in wines built for the long haul.

Clare Valley Rieslings are as breezy and refreshing as a fresh squeezed lime. They often exhibit aromas of granny smith apple and fresh cut flowers6 with a citrus zest finish. These wines also have a fantastic reputation for aging, packing some honeyed density onto their stony frame as the years flash by.

[6] And fresh tennis balls, if Ian Cauble MS of SOMM fame is to be believed.

And Beyond

These are just a few of the wine regions that produce fantastic Riesling. Washington has a long history with the grape, and there are more than 6,000 acres planted here today. Riesling’s cold hardiness (and general deliciousness) has made it the grape of choice for emerging and marginal regions, whether in Michigan, Vermont, or Poland. For myself, I know that as the days get longer and the sun hangs around, I’m going to be reaching for a bottle of Riesling. The saying goes that we talk dry but drink sweet. I think that now especially is the time to talk sweetly...and drink it dry.

Pink Bubbles

Pink Bubbles – Always a Party

Everyone loves pink bubbles. Full stop. It could be the illustrious Rosé Champagne Billecart-Salmon, or it might be sparkling rosé from an aluminum can - you know everyone’s having a good time when the pink bubbles come out. We could all use a little sparkle right now, so here are three of our favorite sparkling rosés from Italy and France.

A view of Plouzeau’s estate

The Marc Plouzeau Perles Fines is one of our most popular wines in the shop. We always have one cold, at least when we can keep it in stock. This Cabernet Franc from the Loire simply does everything right. It’s crisp and clean without being angular, smelling like a cherry orchard and tasting of tangerine slices on a grassy picnic. The Plouzeau’s farm their 75 acres organically, including the replanted vineyards of Chateau Bonnelerie, and their attention to detail shows in this bottle.

Chateau Bonnelerie Marc Plouzeau Perles Fines Sparkling Brut Rosé

● Touraine, France

● Organic Vineyard with biodynamic principles

● “The bouquet shows lovely Cabernet Franc character in its mix of white cherries, a touch of tangerine, currant leaf, lovely soil tones and a bit of smokiness in the upper register.”

● Translates to “tiny pearls”

● Chateau Bonnelerie replanted its vineyards in 1976

● 100% Cabernet Franc

● 30 ha

● Traditional method sparkler

A view from Vielle Ferme

Further south, the Perrins of Chateau de Beaucastel also know a thing or two about growing tasty grapes. They source the grapes for La Vielle Ferme (“the old farm”) from limestone soils in Ventoux and Luberon. Both of these appellations on the border of the southern Rhone and Provence are known for their high quality/price ratio. Grenache, Cinsault, and Pinot Noir are direct pressed (rather than bled off via the saignee method) to stainless steel, producing an airy, citrusy sparkler that won’t weigh you down.

La Vielle Ferme Sparkling Rosé

● VdF, France

● Perrin family, 1970 started importing

● Grenache, Cinsault, some Pinot, direct press

● Limestone

● Stainless steel

● A nose of fresh red fruit (raspberry, wild strawberry) gives way to a palate of citrus(pomelo) and white flowers. [A field with a mountain in the background Description automatically generated]

A view from Tenuta Maccan

Rounding out the parade of pink is the Le Monde Pinot Nero. First of all, Pinot Nero is a way cooler name than Pinot Noir (even if the Nero emperor sucked). This Friulian wine continues the theme by punching way above its weight. It is harvested early to preserve freshness, fermented dry, then refermented in tank using the Charmat method. It stays on the lees for 60 days, picking up a little extra breadth via autolysis, before it is bottled at spumante pressure with less sugar than most brut Champagne. It has round raspberry fruit and a soft, ticklish texture that demands sunshine and a yard.

Le Monde Pinot Nero Rosé Sparkling, Tenuta Maccan

● Friuli Grave, Italy

● 100% Pinot Nero

● Estate owned by Tenuta Maccan

● Charmat method, 60 days on lees

● Vine age 39 years

● 8 gram residual sugar/liter

● Gravel, clay, and calcareous soils

● Founded in 1970

Limestone

Talking dirty about limestone…

Vineyard planted on limestone, Celler de Capcanes

Limestone, Celler de Capcanes

Limestone, Calera Winery

Winemakers can be a dirty lot. Sticky hands, purple feet, muddy vineyard trucks, the whole romantic shebang. A winemaker once told me a story of falling fully clothed into a one-ton fermenter, hosing himself off, driving home to change clothes, then coming back to the winery to finish punchdowns. Winemakers also love to talk dirt. To make wine is to be an amateur geologist, to know your water holding capacity, your soil temperature, your proportion of silt to sand or clay. The residents of the Mosel are very proud of their slate, 1 and the folks in Sonoma love Goldridge loam, but there’s one kind of dirt that fascinates the winemaking world above all others: limestone.

Limestone is made of dead dinosaurs. Ok, not really dinosaurs, 2 but that got your attention better than, “limestone is made of ancient dead pond scum,” even if that’s much closer to the truth. Limestone forms when tiny little creatures (corals, mollusks, etc) living in warm, shallow seas precipitate calcium out of seawater. Often, they use this calcium to build themselves a home (also known as a shell). When this calcium becomes a rock, it is called limestone. 3 The clay-rich limestone marls of Chablis and Sancerre, the Kimmeridgian soils, have visible prehistoric oyster shells in them. Limestone is also found in the Aube, in Piedmont, Alsace, Montsant, Saint-Emilion, and sections of California’s Central Coast. 4 There are many technical ways that limestone affects a vineyard, 5 several of which are still debated today, 1000 years after monks began classifying Burgundy’s many limestone-rich crus.

While the superiority of limestone terroir is far from a settled subject, it is indisputable that winemakers continue to seek it out. The draw of limestone has led successive generations of Californian winemakers to strike out for previously unexplored regions. In the late 1970’s, after several internships in Burgundy, 6 Josh Jensen spent years searching California for limestone soils. He found his slice of golden pond scum on Mt. Harlan, 7 where he would plant his estate vineyards and establish Calera winery. A decade later, the Perrin family of Chateau Beaucastel in Châteauneuf du Pape partnered with the Haas family to found Tablas Creek on a chalky series of hills in Paso Robles. 8 A decade after that, the Stolpmans would establish Stolpman Vineyard on a different piece of calcareous rangeland, this time in Ballard Canyon.

New World winemakers chase limestone because so many of the great vineyards in Europe are planted on limestone soils. What would the wines of the Cote d’Or be without limestone? 9 The cooperative Celler de Capcanes in Montsant has tried to quantify the differences between soil types by vinifying Grenache grown on four very different soils (slate, sand, clay, and limestone) in exactly the same way, then bottling each example separately in their Terroir Workshop line. They claim that their limestone bottling is fresher and more floral than their other wines. 10 Grab a bottle with our new Spanish bundle and see if you can taste the difference.

[1] Be it red or blue.

[2] Though the Jurassic period was named after the limestones of the Jura, where it was first identified.

[3] I am also a rank amateur geologist, so if this is offensively simplified, I apologize.

[4] There is even a deep calcareous layer in Walla Walla silt loam.

[5] Calcium availability, water retention, and grape ph, just to name three.

[6] Romanee-Conti and Dujac. Not a bad resume for pinot noir.

[7] Right next door to the appropriately named Lime Kiln Valley AVA, home of old vine Mourvedre from 1922.

[8] Calera and Tablas Creek have something else in common - they both have clones or vineyard selections named after them. Tablas Creek, unhappy with the available budwood at the time, imported selections of all 13 Chateauneuf varieties. The Calera “clone” of Pinot Noir was either smuggled into the country from the vineyards of DRC or selected by Jensen from heritage cuttings at Chalone.

[9] Or clay, for that matter.

[10] Which mirrors the results of a Decanter tasting of Languedoc wines grown on limestone vs schist.

Mencía

On zombie vines, wine wizards, and fresh ground pepper…

Mencía in Ribeira Sacra, from Jose Pastor Selections

Descendientes de J. Palacios, from Rare Wine Co

Descendientes de J. Palacios, from Rare Wine Co

Raul Perez, from Skurnik

Mencía’s story will sound familiar to anyone who has navigated the wine industry’s constant, churning search for “The Next Big Thing!!!” 1 Old vines in a forgotten region: formerly overcropped, but returned to balance through the reticence of many decades, rediscovered and transformed by (often young) trained vintners searching for value outside of more established 2 regions. In the last 20 or so years, Mencía has been brought back to life by these wine wizards, some of whom3 famously sport preposterously mage-like facial hair. What is old is always new again, and what is considered unknown is still very familiar.

Mencía grows throughout northern Portugal4 and northwestern Spain. This region (the part of it that is in Spain at least) is sometimes known as Green Spain. It’s not the brutal (though still beautiful) Martian landscape of Priorat, nor the continental plains of Rioja. It is oceanic and verdant (In a word - wet). Red grapes grown in cool, wet climates at the margins of their ability to ripen, like Cabernet Franc from the Loire and Syrah from the far Northern Rhone, often exhibit more savory spice than those grown in more comfortable conditions. Fans of these reds will find their first glass of Bierzo or Ribeira Sacra5 hauntingly familiar, because Mencía has more spice than Paul Atreides.6 In fact, the aroma and taste of Mencía is often compared to a hypothetical cross between Cabernet Franc and Syrah, with a bit of Pinot Noir thrown in for good measure. It combines the fresh ground black pepper of cool climate Syrah with the autumnal cassia and herby bark spice of ripe Loire Franc. There are flowers too, and summer raspberries, but it’s that spice that lights me up every time.

Mencía first came to the greater wine world’s attention in the late 1990’s, when Priorat savant Alvaro Palacios and his nephew Ricardo established Descendientes de J. Palacio in western Bierzo. Alvaro had already helped to resurrect another Spanish region, Priorat, in the previous decade, and he saw many of the same building blocks in Bierzo. Their Petalos bottling, 95% Mencía, remains one of our favorite budget friendly reds from anywhere in the world, and their smaller production wines such as Corullon showcase Mencía’s impressive ability to age.7

If the Palacios family brought the world’s spotlight to the wines of Green Spain, then Raul Perez brought the mystery. Did he really age his Albariño at the bottom of the ocean? Did he really macerate his reds for months on end in his cave bear cellars?8 And, most importantly, what was he hiding in his Gandalf meets Dumbledore by way of Rasputin beard!?!9 If his Mencía is any indication, my guess is a pepper mill.

[1] See also - Etna, Tenerife, Mendocino County, Contra Costa, Chilean Pais, Muscadet, Mondeuse from the Savoie, Priorat, Beaujolais, the Rousillon, Sierra de Gredos Garnacha, etcx1000

[2] expensive

[3] Well, one in particular, but more on him later.

[4] Where it is known as Jaen

[5] There are also excellent versions being made in the new world, particularly in the Columbia Gorge by shop favorite Analemma.

[6] I’ll save my sandworm jokes for the next time we feature Chateau Rayas.

[7] I’ve had 10 year old examples that still needed hours in the decanter to fully open.

[8] With no sulphur additions to boot

[9] His nickname in Spain is “mago de los vinos”, or wine magician

Thoughts on the Loire Valley

Chenin Blanc

Harvest at Domaine du Viking

Harvest at Domaine du Viking

Silex flint soils at Domaine du Viking

Silex flint soils at Domaine du Viking

Plowing at Huet

Plowing at Huet

Quick, name the most versatile wine grape you can think of. A grape that conjures operatic roars from traditionalists, yet also makes the hipsters quit slouching and sit up in their 1chairs. A grape whose dry wines offer depth and lift in equal measures, like lightning striking the ocean. Whose sweet wines can last for generations 2. A grape that makes brilliant sparkling wines with pedigree, age-ability, and vintage statements. A grape that was planted extensively in eastern Washington during the early years of vineyard establishment, championed by Walter Clore. This grape, of course, is…

Shouts from the assembled digital crowd - “Riesling!!!”

Chenin Blanc!

Ok, you’re right, I forgot about Riesling. Fine, Chenin Blanc is one of the most versatile wine grapes. Would you like wines of “punk rock violence, yet of Bach-like logic and profoundness”, to quote the estimable Becky Wasserman? Chenin can do that. Do you need a vine you can crop at 10+ tons/acre while maintaining acidity? Chenin can do that too, Mr. California Chablis. The Dutch brought Chenin Blanc to South Africa in the 17th century to ward off scurvy and boredom, and it is still the most planted variety in that country. The Central Valley of California crushed 300,000! 3tons of Chenin in the late 80’s. From stubby bush vines in the deserts of the Swartland, to tight, temperate rows in the Willamette Valley, Chenin Blanc can go anywhere and be anything.

Though it travels well, the Loire Valley is Chenin’s home. There are references to it as far back as the 9th century, which, I am told, was a very long time ago. If the Loire is its home, then the village of Vouvray is Chenin’s bedroom, complete with Ramones posters and Dead Kennedys stickers. The ultimate punk rock empress of wine, one Jancis m-fing Robinson MW, wrote in her mandatory tome The Decline of Western Civilization 4, “Vouvray is Chenin Blanc, and to a certain extent, Chenin Blanc is Vouvray.” Vouvray contains all of Chenin’s multitudes 5 (dry, off-dry, sweet, very sweet, sparkling, red 6), as well as many of its greatest individual expressions. The biodynamic wines of Domaine Huet are probably the most famous in Vouvray. They cover the full stylistic range, and their sweet wines are especially well known for their capacity to age. Their vineyards, planted on the soft local limestone known as tuffeau and harvested in multiple passes (or tries), produce what many would consider the archetypical moelleux (soft, aka sweet) Vouvray.

The Chenin vines of Domaine du Viking dig through hard silex flint that is only found in the very north of the appellation. There, Francoise and Lionel Gauthier vinify their Vouvray in the sec tendre style (tender dry), similar to a halbtrocken Riesling. There is some residual sugar here, but it is well balanced by Chenin’s brilliant acidity. The Domaine’s importer has this to say of Lionel Gauthier’s winemaking prowess - “It can be said without any equivocation that Lionel Gauthier can eat more sweetbreads than you can.” A glowing endorsement if I ever heard one.

Chenin’s versatility lies with that acidity. If picked underripe, it can be bony and puckeringly tart7. It maintains this acidity late into the season while adding heft and curves to its bones, draping itself in waxy pome fruit while never losing that structural framing. The best Chenins are like an orchard next to an apiary, or like you thought a quince might taste before you’d actually tasted one. Botrytis might bring ginger and honey to the party, and the low so2 crowd might bring mixed nuts, but Chenin will bring acidity with it wherever it goes.

Notes From the Author

[1] Ok, you caught me, “our.”

[2] The 1947 Huet was named one of the 100 greatest wines ever by Decanter magazine.

[3] That’s 40,000 more tons than all of the grapes crushed in Washington in 2018, our largest harvest ever.

[4] Or was it The Oxford Companion to Wine?

[5] I believe Walt Whitman wrote I Sing the Body Electric while sipping a particularly glowing Vouvray

[6] Jk, although the rare red grape Pineau d’Aunis is sometimes known as Chenin Noir

[7] “One of the nastiest wines possible” according to Oz Clarke.

Sauvignon Blanc

Monts Damnes

Monts Damnes Photo Courtesy of Rare Wines

Photo Courtesy of Rare Wines

Monts Damnes

Monts Damnes

This is the story of a vineyard in Sancerre that has been forgotten in plain sight. A vineyard that checks all of the great terroir boxes: originally planted in the 10th century by very thirsty Benedictine monks, precipitously steep south-facing hillside that wouldn't look out of place in Cote Rotie or the Mosel, bright white limestone soils1studded with freakin’ fossilized sea shells2, old vines tended by hand out of necessity on said black-diamond steep hill, with a name like a Norwegian metal band, in the best village in one of the best regions for white wine in all of France. Somehow, wines from the vineyard of Les Monts Damnes, translated literally to the Damned Mountain, the greatest terroir in Chavignol, are criminally undervalued. For now.

Outside of the wines from a couple of visionaries like Didier Dagueneau and Edmond Vatan3, very few wines from Sancerre are considered vin de garde. Most Sancerre is fresh and immediate, as easy to slurp as it is to pronounce, and we love it unabashedly. The wines from Monts Damnes are different animals altogether. It starts, as always, with the vineyard. As mentioned, the slopes of Monts Damnes are so steep that some producers provide cushions for their pickers to sit on while they slide down the hill. It’s a hill made for skiing4 rather than planting, and many vignerons allow grass cover crops to grow between the vines to prevent erosion. The southern aspect and extreme pitch maximize sun exposure for the vines, allowing for greater ripeness than in the flats of Touraine.

Producers use more wood for fermenting and aging Monts Damnes than in the rest of Sancerre. Young Matthew Delaporte of Domaine Delaporte uses large format5 used oak barrels on his Monts Damnes. His family has operated in Chavignol for more than 300 years, but the 31-year-old winemaker refuses to rest on his laurels, converting his vineyards to organic certification6, allowing full malolactic fermentation, and extending the lees aging of his finest cuvees up to 12 months. His tweaked vinification, which mirrors the efforts of regional stalwarts like the Cotat cousins Francois and Pascal, embraces the substance and heft that this site provides.

Accordingly, the wines from Mont Damnes are richer than your typical gooseberry and nettle Sancerre, with yellow fruit, ripe citrus, and a resinous density that would not seem out of place in good white Burgundy. This is the sort of lazy comparison that normally drives me crazy, a shorthand way of saying that this white wine is delicious and complex now and will remain delicious and complex for several more years, but I just can’t shake it. And maybe I shouldn’t. Chavignol is closer to Chablis than it is to Nantes. The soils are the same, clay and limestone marl over an ancient seabed. Most importantly, the wines of Monts Damnes, like the wines of Les Clos, taste more of the place they are from than the grape they are made of. Les Clos doesn’t really taste like Chardonnay, it tastes like Les Clos. Monts Damnes doesn’t taste like Sauvignon Blanc. It might not even taste to you like Sancerre. More than anything, it tastes like the Damned Mountain.

Notes From the Author

[1] Terres blanches, the same soils as Chablis, which is less than 75 miles away.

[2] That everyone says you totally can’t taste, but the itty bitty shells are right there, and it’s so rocky, and naaah naah naah, I can’t hear you, minerality, minerality, minerality! Ok, fine, it tastes salty. Happy?

[3] Both of whom source their Sancerres from Monts Damnes

[4] Imagine slaloming among meter by meter plantings of old vine Sauv Blanc!

[5] 600l demi-muids

[6] “We have also stopped feeding the vines like at McDonalds.” - Matthew Delaporte

Muscadet (Melon de Bourgogne)

Photo Courtesy of Weygandt-Metzler

Photo Courtesy of Weygandt-Metzler

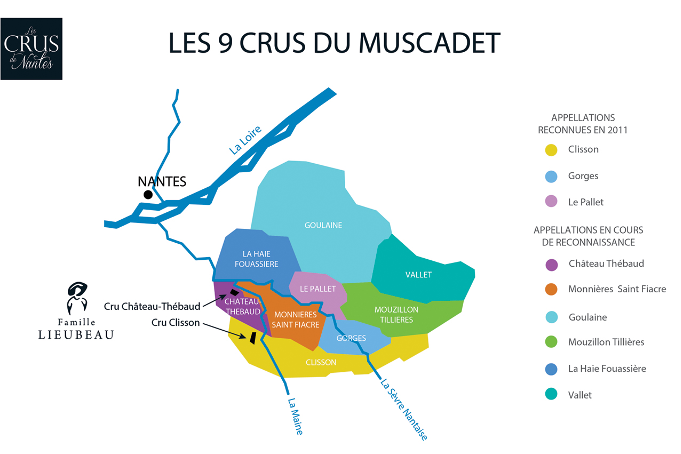

Muscadet, for better or worse, has been defined by what it is not. Not heavy, not oaky or buttery, not overly fruity, certainly not expensive. A neutral, rather than aromatic, white. A wine so transparent that it is best known for the turbid solids that it ages beside, the pillowy spent yeast cells of sur lie aging that are cast aside at bottling. Muscadet can be ephemeral if it is treated dismissively, seeming to exist only in the spaces between oysters. Its transparency, though, is also its greatest strength, enhancing and exaggerating the regional differences among Muscadet’s 9 newly established crus like a terroir-magnifying lens.

Muscadet only has one grape - Melon B, formerly Melon de Bourgogne. This lattter name was confusing for several reasons1, not the least of which being that Melon is not grown in Burgundy, at least not anymore. Melon’s tumultuous relationship with, and eventual banishment from, Burgundy mirrors another of our favorite grapes: Gamay. You could say that they both got Beauned. Gamay was famously cast out of Burgundy by Phillipe the Bold in 13952, while Melon lasted until the 18th century before being evicted because of overproduction3. Melon and Gamay didn’t just get kicked out of the same childhood home; in fact, they’re siblings! Melon, Gamay, Chardonnay, Aligoté, and countless other varieties resulted from crosses between the aristocratic Pinot4 and the nearly extinct Gouais Blanc, which was a grape of the peasantry.

While Gamay was able to find a new home just to the south of the Cote d’Or, Melon landed 600 km west, as if Burgundy tried to throw it into the Atlantic Ocean and came up just short. Here, in one of France’s most marginal climates, Melon’s productivity and hardiness were welcomed by a local wine industry rocked by winter kill. It was here, around the city of Nantes on the coast of Brittany, that Melon met “la mer”.

Wines grown near the ocean, from Ligurian Vermentino to western Sta. Rita Hills Pinot Noir5, often taste salty, and Muscadet is no different. If oysters remind me of eating the ocean, then Muscadet is like drinking it6. When young, its nerviness makes it “the quintessential springtime wine,” according to Richard Hemming MW, a wine that pairs as well with delicate spring produce as it does with Cthulhu pulpo. Save some in your cellar and you will be rewarded with one of the great wine transformations. Aged Muscadet maintains its transparency and vitality while adding a warm sepia lens. Its briny origins and maritime structure remain, though the ocean grows as honeyed and round as if you spun cotton candy from seawater. Muscadet vigneron Jo Landron describes it as, “sugared, but with no sugar.” I can’t help but taste Burgundy by the sea.

Notes From the Author

[1] And has led me down some youtube rabbit holes that started in Muscadet vineyards and ended in a Dijonaise backyard looking at canteloupe.

[2] His description of a “very great and horrible harshness” makes me wish I could pour him a silky, pillowy glass of Lapierre Morgon.

[3] The same complaint levied at Gamay.

[4] Either Noir, Gris, or Blanc, which are genetic variations of the same grape rather than distinct varieties. I’m not an ampelographer, I don’t make the rules.

[5] See also: Santorini, Corsica, Tenerife, Cassis, the west Sonoma Coast, Chile’s Casablanca Valley, parts of Rias Baixas and western Galicia, Madeira, etc.

[6] Do not attempt to drink the ocean.