Our blog was created to help make the world of wine and beer easier to understand and fun to navigate. There are a million things to know in this industry, we just want to help you understand the latest news and trends from around the globe. So sit back with your favorite sip and let's go on an adventure.

Kermit Lynch's Thoughts on Etna's Vigneti Vecchio

Shop our Etna! Vigneti Vecchio 3-Pack HERE

From Kermit Lynch:

While viticulture on the slopes of Mount Etna dates back thousands of years, only in the last decade or two have the wines produced on Sicily’s mythical volcano entered the global spotlight. Eager to exploit the terroir riches of this stunning natural wonder, waves of newcomers from around Italy and abroad have settled, relying on both traditional methods and modern enology to search for Etna’s truest expression.

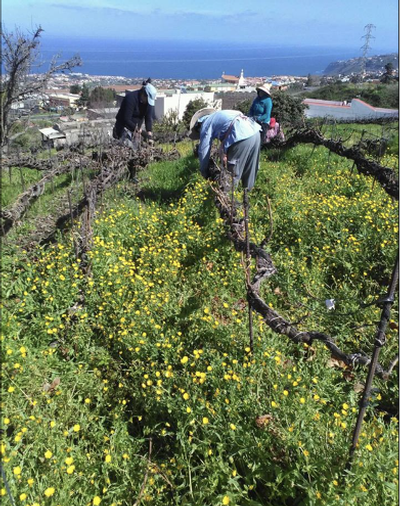

The fascination with Etna in the eyes of growers and consumers alike stems not only from its fertile soils of sandy, decomposed volcanic rock but also from the elevation that allows its wines to retain an uncommon freshness and delicacy at such a southerly latitude. Reaching over 1,000 meters above sea level, Etna’s vineyards are some of Europe’s highest, and the cool nights late in the growing season favor slow ripening and the development of extremely complex aromas at relatively low alcohol levels. Harnessing this potential to create wines of nuance and finesse, however, is another story altogether: it requires vision, dedication, and careful execution. It is with tremendous excitement, then, that we announce our collaboration with Vigneti Vecchio, a small family-run estate on Etna’s northern face.

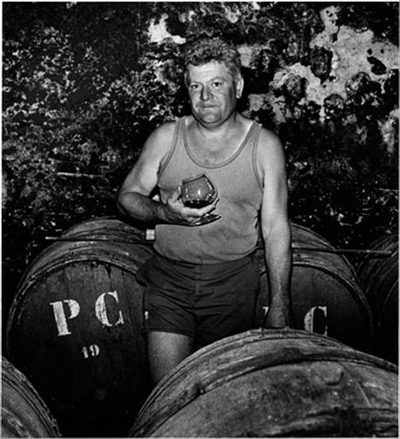

Carmelo Vecchio and his wife, Rosa La Guzza, did not come from afar to make wine on Etna: they are true locals, raised in the heart of the vineyards. Carmelo began working at the nearby Passopisciaro winery at a young age, and after fifteen years of hands-on experience, the time came to strike out on his own. From barely one hectare of vines up to 130 years old inherited from Rosa’s family, the couple took matters into their own hands: sustainable farming by hand, with the goal of achieving an elegant balance in the grapes; micro-vinifications in the tiny cellar beneath their home, with respect for tradition and terroir; and aging the wines in used barrels before bottling without fining or filtration.

Armed with excellent raw materials along with Carmelo's years of experience and an appreciation for ancient local practices such as skin maceration for whites and blending white grapes into the reds, Rosa and Carmelo succeeded in crafting delicate, pure, and highly refined wines from their inaugural 2016 harvest. While Etna still searches for its identity, Vigneti Vecchio demonstrates that this towering volcano rising from the Mediterranean can in fact produce wines as beautifully nuanced as anywhere else in Italy.

Carricante Sicilia Bianco “Sciare Vive” 2018

- 90% Carricante, 10% indigenous varieties (Minnella, Inzolia, Grecancico, Catarratto)

- 3 day skin maceration in stainless steel tank

- Must is pressed, then primary and malolactic fermentation in 500-L oak barrels

- Aged 7 months in 500-L oak barrels on lees

- Racked off lees into stainless steel tank 1 month before bottling

- Wines age in bottle for 1 month

- Does not receive Etna Bianco DOC because one parcel is located just outside the appellation boundary

- Vines planted between 1,600 and 2,800 feet above sea level

- Fennel, pine resin, wildflower honey

Etna Rosso “Contrada Crasà” 2017

- 90% Nerello Mascalese, 10% indigenous varieties (Inzolia, Grecanico, Catarratto)

- Grapes sourced from Contrada Crasà

- All grape varieties are fermented together

- 15-day skin maceration and primary fermentation in stainless steel tank

- Light punch-downs and pump-overs during fermentation

- Must is pressed, followed by malolactic fermentation in 500 L oak barrels

- Aged 9 months in 500-L oak barrels on lees

- Racked off lees into stainless steel tank 1 month before bottling

- Aged in bottle for 8 months

- Vines planted at 2,100 feet above sea level

- Cherry compote, white pepper, ash

Terre Siciliane Rosso “Donna Bianca” 2018

- 50% Nerello Mascalese, 20% Nerello Cappuccio, 20% Alicante, 10% indigenous white grapes

- Vines located in northern Etna, just outside of the Etna DOC

- All grape varieties are fermented together

- Grapes are de-stemmed

- 12-day skin maceration and primary fermentation in stainless steel tank

- Light punch-downs and pump-overs during fermentation

- Aged 9 months in 500-L oak barrels on lees

- Aged 1 month in bottle

- Located at 2,700 feet above sea level

- Red cherry, lavender, rosemary

Shop our Vigneti Vecchio 3-Pack HERE

Thoughts on Whole Cluster Fermentation & Specs About the Package Wines

Whole cluster fermentation is in, destemmers are out (good riddance, as anyone who has cleaned one will agree), and Henri Jayer is rolling in his grave. We’ve discussed the fickle nature of the wine industry on this blog before. There is always a fresh flavor of funky newness coming over the horizon, or an as yet undiscovered wine region (the enological North Sentinel Island) to be both championed and gate-kept by Magellanic sommeliers. Everyone is drinking rosé again, Cru Beaujolais and the Jura have celebrated their time in the sun, and regenerative viticulture is just now entering the cool-wine zeitgeist.

Whole cluster, though, has managed to pervade both the edgy corners of wine nerd-dom and the pillared halls of wine orthodoxy. There are even large national brands advertising whole cluster fermentation on their labels! Unfortunately, the term is not very well understood, and winemakers have confused the issue further by using several different names for the same process (whole cluster/whole bunch/partially destemmed/etc). We want the truth, the whole cluster truth, and nothing but the truth!

What do you mean by whole cluster?

In a typical red wine fermentation, grape clusters are dropped into a destemmer, which removes the stems and spits out clean purple grapes that look like blueberries. Skip this step, and you are left with full clusters of grapes still attached to the stem. These are whole clusters.

Great, we’ve got whole clusters. Now...uh… how do we make them into wine?

Oftentimes these clusters will be crushed and piled into a fermentation vessel. This crushing can be done mechanically, or through the time-honored tradition of foot-stomping (“pigeage”). This releases juice, submerging the solids, preventing microbial spoilage (also known as vinegar).

That sounds easy! Why would anyone ever use a destemmer?

Well, some varieties are not as well suited to whole cluster fermentation as others. Pinot noir, Grenache, Syrah, Mencía, and Gamay are generally regarded as good fits for whole cluster fermentation, but pyrazine-heavy reds like Cabernet and Merlot can become green and vegetal. Stemmy fermentations also require careful tannin management to prevent hard, unyielding wines. Finally, the potassium in stems (as well as any incidental carbonic maceration) causes the pH of the finished wine to rise, which can lead to instability.

Hey, you tried to sneak in a word there! Think I wouldn’t notice?!? What’s carbonic maceration?

Yeesh. Ok. Carbonic maceration is an intracellular fermentation that takes place in an anaerobic environment, usually a CO2-filled tank. Fruity esters, reminiscent of strawberry and raspberry, are produced, and the malic acid of the grapes is degraded, raising the pH. Uncrushed whole clusters are very conducive to carbonic maceration, and almost all of the classic producers of Cru Beaujolais use whole clusters and at least semi-carbonic maceration. This leads to the fruity aromas and silky textures that the region is known for.

Welp, I’m sorry I asked. Ok, I think I’m getting it. If you’re lazy and you don’t want to use the destemmer, you can use whole grape bunches in your wines. That’s whole cluster.

Well, mostly. Remember, a winemaker doesn’t have to leave his entire harvest as whole bunches. Many winemakers will choose to either destem part of a crop or fill a fermenter with alternating lasagna layers of destemmed grapes and whole clusters or destem the whole crop and then add back in some of the de-graped stalks. Domaines in Burgundy will often vary the amount of whole clusters from vintage to vintage, with a poor or rainy vintage usually getting less while a warm solar vintage gets more. It’s just another wrench in the winemaker’s toolbox.

So, whole cluster usually means not de-stemming grapes, except when it doesn’t. Got it. Very clear cut. Thanks for all your help. What do these Schrodinger wines taste like? Both wine and not wine at the same time, until you drink them?

*Oblivious to sarcasm* You’re very welcome. They taste delicious! Yes, sometimes they can be a little...ahem…stalky, but in the hands of a sensitive winemaker, stems can add lift, spice, and resinous snap. The best way to understand the impact of stems is to try two different wines, one whole cluster and one destemmed, from the same producer or region. Maybe try a rustic, spicy, whole cluster Cornas next to a suave, fudgy, destemmed Hermitage. Ask your local wine purveyor to help you pick out a wine with whole clusters and see what all the cool wine kids are excited about.

GLOBAL DRINK WINE DAY PACKAGES

Whole Cluster, Cozy Reds 3-Pack, Shop Here

Castro Candaz Tinto 2019

- Ribeira Sacra, Galicia

- Primarily Mencia, with Domingo Pérez (Trousseau), Garnacha Tintorera (Alicante Bouschet), Mouratón, Caiño and Brancellao

- Organic viticulture

- 100% whole cluster fermentation in wooden vessels

- Aged in 500l barrels and foudre

- Raspberry, red cherry, bergamot

Domaine de la Grosse Pierre Chiroubles “Claudius” 2018

- Chiroubles, Beaujolais

- 100% Gamay noir au jus blanc

- Pink granite

- 80 year old vines

- 3800 vines per acre

- 100% whole cluster, semi-carbonic maceration

- Fermented 12 days with one pump over per day, native yeasts

- Aged 11 months in concrete tank

- Unfined, unfiltered, no SO2 until bottling

- Blackberry, black cherry coulis, cracked black pepper

Eric Texier Domaine de Pergaud Vieille Serine Brézème 2014

- Brézème, Ardeche

- 100% Syrah (Serine)

- ~90 year old vines

- Limestone soils

- Organic viticulture, incorporating no-till and compost tea preparations

- 100% whole cluster fermentation with submerged cap for 5-7 days

- Aged 3 years in foudre with no racking

- No punchdowns or pumpovers

- Unfined, unfiltered, no added SO2

- 93 points John Gilman

- Cassis, smoked brisket, salt-cured olive tapenade

International Chardonnay: Winter Whites 3-Pack, Shop Here

Edi Kante Chardonnay 2016

- Venezia Giulia, Friuli

- 100% Chardonnay

- Clay and limestone

- Fermented and aged 12 months in old barrels

- Aged 6 additional months in stainless steel

- Bottled unfiltered

- Orange blossom, lemon curd, clove

Dominique Lafon Bourgogne Blanc 2018

- Burgundy, France

- 100% Chardonnay

- Clay and limestone

- Organic viticulture

- 20-50-year-old vines sourced from Meursault and Puligny-Montrachet

- Whole cluster pressed

- Fermented and aged for 12 months in old barrels, native yeasts

- Little or no battonage

- White peach, Meyer lemon, crushed chalk

Crossbarn Sonoma Coast Chardonnay 2018

- Sonoma Coast, California

- 100% Chardonnay

- Hand-harvested at night

- Whole cluster pressed

- Fermented and aged in 90% stainless steel, 10% neutral oak barrels

- Aged 5 months on the lees

- 92 points JS, 90 points WA, 90 points JD

- Sliced apple, nectarine, wildflower honey

Rhône or Bust Syrah 3-Pack, Shop Here

Patrick Jasmin “La Chevaliere” 2016

- Collines Rhodaniennes, Northern Rhône

- 100% Syrah

- Decomposed granite and schist

- Sourced from the plains below Côte Rôtie

- 100% destemmed

- 20-22 day fermentation with punchdowns

- Aged 12-18 months depending on vintage

- Red plum, bresaola, sandalwood

Equis Equinoxe Crozes Hermitage 2017

- Beaumont-Monteux, Northern Rhône

- 100% Syrah

- Gravel and loam

- Practicing organic

- Fermented in wood and concrete with native yeasts

- Aged in 40hl tronconique wooden vessel

- Black currant, blackberry, anise seed

Domaine Rostaing Les Lezardes 2018

- Collines Rhodaniennes, Northern Rhône

- 100% Syrah

- Fruit sourced from the northern edge of Côte Rôtie, as well as Tupin

- Majority whole cluster fermentation for 7-20 days

- Aged in older barrels, many demi-muid

- 90-91 points VM, 89-91 points JD, 89-91 points WA

- Blueberry, allspice, wild boar bacon

Italian Dinner Party 6-Pack

SHOP ITALIAN DINNER PARTY 6-PACK HERE

La Valle Del Sole Offida Pecorino DOCG 2018

- Piceno, Le Marche

- 100% Pecorino

- Organic certification since 1990

- Clay and sand

- Destemmed, 12-24 hours of skin contact

- Fermented in stainless steel

- Aged in concrete, 6 months on lees

- White grapefruit, jasmine, sea spray

Bonnaccorsi ValCerasa Etna Bianco DOC Carricante 2016

- Northeastern side of Etna, in Crucimonaci between the Passopisciaro and Randazzo contradas.

- 500-850 meters elevation

- Down the road from Tenuta delle Terre Nere

- Learned from Salvo Foti

- 37 acres

- Organic farming

- 100% Carricante

- 2 years in stainless steel, some battonage

- Lemon peel, raw almond, smoked salt

\

\

Castello di Volpaia Chianti Classico 2018

- Tuscany

- 90% Sangiovese, 10% Merlot

- Certified organic

- Sandstone and clay

- Fermented in stainless steel

- Aged 12 months in Slavonian oak

- 93 points JS, 92 points VM, 91 points WE

- Red cherry, plum skin, iron shavings

Gabbas Lillove Cannonau di Sardegna 2018

- Sardinia

- 95% Cannonau (Grenache), 5% Muristellu

- Fermented for 12-15 days in stainless steel

- Aged in stainless steel

- Raspberry, violet, slate

Botromagno Primitivo 2018

- Gravina, Puglia

- 100% Primitivo (Zinfandel)

- Calcareous clay and gravel

- 45-year-old vines

- Fermented 10 days in stainless steel with gentle pump-overs

- Aged 12 months in stainless steel

- 90 points WE

- Blackberry, hibiscus, loam

Fattoria del Cerro Vino Nobile di Montepulciano 2016

- Montepulciano, Tuscany

- 100% Prugnolo Gentile (Sangiovese)

- Largest private estate in Montepulciano

- Fermented at 75-82 degrees

- Malolactic fermentation in large format oak

- Aged 18 months in large oak

- 90 points WE

- Black cherry, cassis, eucalyptus

SHOP ITALIAN DINNER PARTY 6-PACK HERE

New @ The Thief: José Pastor Selections

SHOP JOSÉ PASTOR SELECTIONS HERE

Spain’s Etch-a-Sketch

Let’s see, what do we have here? *digs through cases of newly arrived wine* Ah, yeah, pretty standard stuff: a grape no one has heard of, grown on the side of a volcano off the coast of Africa, a zero-sulfur blend from the suburbs of Barcelona, a Rioja that tastes like it came from the Loire, a natural pet-nat from Mexico’s Marcel Lapierre, and a Chilean Pinot Noir fermented in a cowhide. Just another day at The Thief.

What do all of these wines have in common? They’re all imported by José Pastor Selections, a relatively new discovery that has been shaking the heck out of the Spanish speaking wine world’s Etch-A-Sketch. From fresh updates to classic regions like Rioja or Ribera del Duero, to undiscovered treasures in the Canary Islands and Mexico, Pastor’s wines share a commonality of sustainable viticulture, low-input winemaking, and vivaciousness, coupled with an uncommon (in the natural wine world) rigor of cleanliness, clarity, and typicity. The wines from four-way collaboration Envínate have received a fair bit of press already (and remain some of our favorites in the portfolio), but there are plenty of other fascinating producers. Let’s meet a few of our favorite new faces...

DOLORES CABRERA

José Pastor is possibly best known for contributing to the popularity of wines from the Canary Islands. Tenerife, the largest and most populous island, lies 200 miles off the coast of Morocco. Here, Dolores Cabrera organically shepherds centenarian Listán Negro (a variety believed to grow nowhere else) vines trained in the local cordon trenzado braids. Her La Araucaria Tinto cuvee is dark, spicy, and smoky, a common thread for volcanic wines. It is also, at $24, one of the shop’s best values.

AKUTAIN

After stages in some of the most illustrious cellars in Rioja (La Rioja Alta and CVNE), Juan Peñagaricano Akutain began planting his own vineyards. He hoped to recreate the classic wines of the region with exacting micro-cuvees, rather than the domineering omnipresence of the larger bodegas. If his 2018 Consecha is any indication, he might be outstripping the larger houses. A crunchy, fragrant, funky joven (young) wine, this is a bistro buster that deserves a hot grill.

BICHI

These might be the first wines from Mexico that the shop has carried! Bichi has only been around since 2014, but they are standing on the shoulders of hundreds of years of local wine production. The winery began as a collaboration between the Tellez family and Burgundian Louis-Antoine Luyt, who is best known for his work with the Mission grape in Chile. Bichi now farms 25 biodynamic acres of vineyards around Tecate, east of Tijuana, and collaborates with local growers on other organic vineyards, striving to produce “vinos sin maquillaje”, or wines without makeup. For the Listán cuvee, 100-year-old Listán Prieto (also known as Mission or País) vines produce tiny yields of concentrated grapes that are then fermented in locally made concrete tinajas. These are culty, hard to find natural wines, and they are going to go quickly.

HERRERA ALVARADO

Carolina Alvarado and Arturo Herrera built their adobe winery by hand, and 15 years later they still do not have electricity. Instead, they rely on traditional enological techniques, including incorporating cowhides in the fermentation of their red wines. This is a cooler part of Chile just north of the Casablanca Valley, where Sauvignon blanc and Pinot Noir reign supreme. Their La Zaranda Sauvignon blanc, named after the local manual destemmer, is macerated for a couple of days before fermenting and aging 17 months in concrete. Bottled without SO2, this is a salty lime and candied jalapeno zinger that has me dreaming of a hot porch and bottomless fish tacos.

SHOP JOSÉ PASTOR SELECTIONS HERE

Cabernet, You Say? Winter Warmer 6-Pack Specs & Photos

SHOP WINTER WARMER 6-PACK HERE

Cousiño Macul Antiguas Reservas 2017

- Maipo Valley, Chile

- Founded in the 19th century and still owned by the original family

- Estate grown

- 7-day cold maceration

- Fermented 10 days

- 20 day extended maceration

- Aged in French oak for 12 months

- 90 points WS

- Dried cherry, white pepper, crushed marjoram

Campo alle Comete Cabernet Sauvignon 2016

- Castagneto Carducci, Tuscany

- Alluvial clay

- Fermented and macerated for 3 weeks in stainless steel

- ½ aged in tank and ½ aged in French oak, some new

- 90 points WE, 90 points JS

- Black currant, blueberry, cedar

Jim Barry The Cover Drive Cabernet Sauvignon 2016

- Coonawarra, South Australia

- Red loam (terra rossa) over limestone

- 21-year-old vines

- Aged 12 months in French oak

- 3.45 ph

- 90 points WE

- Blackberry compote, plum, cola

Smith & Hook Cabernet Sauvignon 2016

- Central Coast, California (San Antonio Valley, Paso Robles, Hames Valley, Arroyo Seco, and San Benito County)

- Barrel fermented

- Aged 10 months in French oak, 60% new

- 3.79 ph

- 91 points WW, 90 points WE

- Black cherry, mocha, vanilla

Sister’s Run Old Testament Cabernet Sauvignon 2016

- Coonawarra, Australia

- 100% Cabernet Sauvignon

- Terra rossa

- Single vineyard wine

- 3.61 ph, 6.01 g/l TA

- 90 points WE

- Blackberry, cinnamon, bay leaf

Secret Squirrel Cabernet Sauvignon 2015

- Columbia Valley, Washington

- Declassified estate fruit from Red Mountain and Walla Walla

- Native yeast fermented

- Aged in French oak puncheons

- 92 points Owen Bargreen

- Cassis, dark chocolate, espresso

SHOP WINTER WARMER 6-PACK HERE

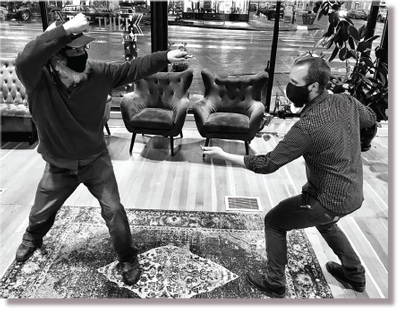

Love & Strife & Spanish Wine: An enlightened philosophical debate – over text - between coworkers...

WARNING: High-level wine nerd content and possible swearing.

ALLAN

The wines you like usually show the worst possible wine flaw - perceptible new oak. They are the Chevy commercial, Bob Seger, unironic denim jackets of wine.

MATT

I have trouble deciding if the wines you like are flawed, or if the winemaker’s mustache wax fell in the barrels.

ALLAN

High alcohol. New oak. Structure you’d be better off chewing than sipping. Not all of us have hearths and overstuffed leather chairs to sit in while we swirl our grape whiskey and think about the Civil War.

MATT

“Natural Wine” is throwing away everything and all the technology to make things better. You probably prefer porn from the 70’s.

ALLAN

“Old school” Spanish wine, especially Rioja, was just mimicking Bordeaux after it was wiped out by phylloxera. Who knows, maybe whole cluster no so2 carbonic zero zero biodynamic dry-farmed no-till regenerative b-corp wines were already a thing before the homogenization. And...uh…uh… Priorat is dumb.

MATT

I think some new-age hipster winemakers heard high VA gets high scores. They should not have set their bar at actual nail polish remover. That wine you made me taste with a “little” brett would pair nicely with filet mignon and a horsesh&% demi-glace. BTW, it was so underripe the side of green beans tasted more like grapes than the wine did.

ALLAN

Syrup is for pancakes, not Syrah, score-chasing is for people who don’t know enough to trust their own palate, and, to quote Sideways, “I will not be drinking any fucking Russian River Pinot!”

MATT

Flashy labels are for beer. You can f&%* beer up and brew another batch. You would think after making a bulls$%# wine and wasting an entire vintage, one would learn, but no, they just got stoned and thought mother earth would come and save the day.

ALLAN

Michel Rolland and Robert Parker were the vinous equivalent of a human centipede. Is this Carmenere, Merlot, or Malbec? Who knows? It smells like prune juice and tastes like it was made by a 10-person committee at Budweiser. I bet you like Crocs.

MATT

I once heard winemaking was like going to battle with microbiology. Apparently, your wines are like the French, just not like French wines.

ALLAN

Look, I’m sorry your wines haven’t been cool since Carson Daly was a thing. You and I both know that these things go in cycles. Pet-nat and carbonic maceration are cool right now, but by the time your daughter is drinking wine, the hot new thing will be Elon Musk’s Martian Merlot, or Botswanan Acacia Vermouth, or skin-contact Viura fermented in a burned-out Terminator exoskeleton. What I’m trying to say is this - even then, your wine still won’t be cool.

---

We haven’t come to a compromise, but one thing is for sure: we would both happily share a bottle of Vega Sicilia Unico Reserva Especial. As long as the other one is picking up the tab.

---

NOTE TO READER: Do not attempt to buy either of these bearded gentlemen Vega Sicilia Unico. They’ll just find a reason to make fun of you.

BATTLE SPAIN 3-PACKS

BIG & BOLD (Matt), SHOP HERE

AVANT-GARDE (Allan), SHOP HERE

Alto Moncayo Veraton Garnacha 2016

- Campo de Borja

- 100% Grenache

- 30-50-year-old vines

- Aged in a mix of French and American barrels for 16 months

- 80% new oak

- 94 points JS, 91 points WA, 90 points WE

- Blueberry, blackberry, vanilla

Bodegas Breca Old Vines Garnacha 2017

- Calatayud

- 100% Garnacha de Aragón, the oldest clone of Garnacha in the world.

- 1925-1990 (The majority of the vineyards are planted between 1965 & 1990)

- Dry farmed

- Practicing organic

- Fermented in stainless steel using pied de cuve

- Aged 18 months in used 500l and 600l barrels

- 92 points JS, 92 points JD, 91 points WS

- Red currant, mocha, licorice root

Marques de Murrieta Rioja Reserva 2015

- Logrono, Rioja

- Bodega founded in mid 19th century

- 80% Tempranillo, 12% Graciano, 6% Mazuelo, 2% Garnacha

- Fermented in stainless steel for 8 days

- Aged 2 years in American oak, 1 ½ years in bottle prior to release

- 93 points WA, 93 points JS, 92 points WS (#40 Top 100 Wines 2019), 92 points W&S

- Dark cherry, cedar, cardamom

Commando G La Bruja de Rozas 2018

- Vinos de Madrid, Gredos

- Garnacha

- 50-80-year-old vines

- 2800’ elevation

- 40-60 day maceration, native yeast fermentation

- Aged 9 months in 30-60HL oak vats

- 95 points JS, 94 points WA

- “They seem to go from strength to strength and are getting closer to their goal with some of their wines achieving world-class status! One of the most exciting new projects not only in Gredos but in the whole of Spain!” Luis Gutierrez, Wine Advocate

- Blackberry, slate, cracked Tellicherry pepper

Envinate Garnacha Tintorera Albahra 2019

- Vino de Mesa

- 75% Garnacha Tintorera (Alicante Bouschet), 25% Moravia Agria

- Practicing organic

- 30-year-old head-pruned vines

- Fermented 50% whole cluster with native yeasts in 45HL concrete tanks

- 7-day maceration

- Aged 8 months in same concrete tanks before bottling with low SO2

- 94 points WA

- Cherry skin, crushed rose, Tasmanian pepper berry

Goyo Garcia Viadero Joven de Viña Viejas 2018

- Ribera del Duero

- 100% Tempranillo

- 40-year-old vines

- Organic viticulture

- Fermented in stainless steel with 3-month maceration

- Aged entirely in tank, no oak

- Bottled unfiltered, unfined, and with no additional SO2

- Tart plum, pressed violet, Lapsang Souchong

A Tour of South African Wine Regions

South Africa is in the midst of a wine renaissance. Gone are the days of tarry Pinotage and insipid, over-cropped Chenin Blanc. The new South Africa has tension, verve, and style to spare as young producers chip fresh regional identities from unforgiving sandstone, granite, and shale. Ent-like old vines are finding contemporary homes, while acres of young vines are planted in wine regions that hardly existed 15 years ago. The shop just received a baboon-load of very exciting South African wines, so let’s take a tour of the wheres-its and wines of the Western Cape.

Stellenbosch

Just a few miles east of Capetown, Stellenbosch is the most planted wine region in South Africa, with almost 20% of the country’s vineyards. The weather is hot and dry, allowing local vintners to ripen a wide range of varieties with low disease pressure. Cabernet Sauvignon is the most widely planted variety, followed by the aforementioned, much-maligned Pinotage. The blistering heat is moderated by proximity to the ocean, and some vineyard owners are expanding their plantings of white varieties close to the ocean. Mick and Jeanine Craven source their skin contact Pinot Gris from an eastern facing site in Stellenbosch, fermenting it like a red wine in open bins with pump-overs and punch-downs. Pale red in the glass, with hints of cherry and watermelon, this will upend your preconceptions about both South Africa and Pinot Gris.

Swartland

The Swartland, northwest of Stellenbosch on the western edge of the Cape, was traditionally a wheat-growing country rather than a source for fine wines. The vineyards of the region were rustic and overcropped, with many of the grapes going to co-ops or fortified wine production. Eben Sadie, of Sadie Family Wines, was one of the first winemakers to see the region’s potential, moving there in 1997, and now the Swartland is one of the most important wine regions in South Africa. Sadie’s spicy Rhone reds and complex, old vine whites (check out the Palladius, a blend of almost a dozen different varieties) have become benchmarks for the Swartland, as well as for South Africa as a whole. Old bush vine Chenin blanc is also one of the region’s signatures. Check out the Storm Point Chenin Blanc for a firm, lemony expression, or try the A.A. Badenhorst Secateurs for a richer straw and lanolin bottling that recalls Vouvray.

Hemel-en-Aarde

As South Africa’s warmer regions began to receive acclaim, producers have pushed towards the coast, seeking more marginal maritime climates that extend the growing season and allowing them to focus on cooler climate varieties like Pinot noir and Chardonnay. Hamilton Russel’s founders were among the first to plant the Hemel-en-Aarde Valley (which means heaven and earth) back in the mid-’70s. Today many other producers have followed them to the southern end of the Cape. Pop a bottle of Lelie van Saron Syrah from Natasha Williams for an iron-flecked, darkly fruited spice bomb.

Songdagskloof

Just north of the Hemel-en-Aarde (to be fair, almost everything is north of there) is the new, hard to pronounce region of Songdagskloof. The soils here have more clay, which slows ripening further. The region has become known for its lean, aromatic Sauvignon Blanc. Trizanne Barnard ferments half of her Songdagskloof Sauvignon blanc on the skins, creating texture and pithiness, while she whole cluster presses the other half for a more traditional white expression. The result has all the citrus lift and phenolic bite of a half-peeled white grapefruit.

Elgin

Johan “Stompie” Meyer battles elevation, baboon raids, and unforgiving shale soils to craft crunchy, whole cluster, low sulfur Pinot noirs in one of South Africa’s most exciting new regions. His new plantings are cooler and higher than almost any other vineyards in the country, and a snappy acidity and arcing energy pervade his cuvees. His Palmiet is red-fruited and chewy, with black cherry skin and anise seed, while his experimental No SO2 and Carbonic cuvees push the limits of zero-gravity raspberry weightlessness. Elsewhere in the Cape South Coast, Thorne and Daughters Copper Pot Pinot Noir offers one of the finest values we carry, with wild strawberry, black loam, whole bunch sap, and real Pinot typicity for only $26.

Bot River

Finally, the Bot River is known for minerally white wines that continue to flip the traditional narrative of heavy, ponderous South African wines. The local scrubland known as ‘fynbos’ provides a resinous thyme and pine herbaceousness, not unlike the garrigue of southern France. The Anysbos Disdit White, a blend of 60% Chenin blanc with Roussane and Marsanne, makes the Rhone comparison explicit, with mouthwatering lemon curd, marzipan, orange zest, raw almond, dry honey, and fresh sage. Can’t wait to try some of their goat cheese!

We have been very impressed by the diversity and ingenuity of South Africa’s winemakers. Much like recent revolutions in well-established new world wine regions like Australia and California, The South Africans are willing to stick to orthodoxy and a safe bet. Let’s raise a glass to the whole cluster stompers, the skin contact-ers, and the terroir pioneers. Cheers!

SHOP THE MIX & MATCH STORM FRONT 6-PACK or CASE deals HERE!

Pairing Wines with Thanksgiving Sides

ROCKIN' REDS FOR THE TURKEY TABLE 6-PACK, SHOP HERE

Not-so-hot take alert - Thanksgiving is all about the sides! Every single one of us has a relative who would commit avian war crimes every holiday season, conducting thermonuclear weapons testing on white meat turkey until it shattered in your mouth. These well-intentioned relatives would sacrifice frivolous, decadent concepts like “flavor” and “texture” in favor of a desiccated Norman Rockwell shell that deflated as soon as Uncle Rob got out the electric carving knife. You and your cousins would duel with salad tongs to see who got the only edible bites of dark meat, while the rest of the family choked down slivers of breast meat. The horror…

Luckily, there were side dishes. Casseroles, mashes, stuffing, and dressing (the difference escapes me, but I haven’t brought it up since Aunt Jacky and Uncle Kevin’s tense ceasefire of ‘97), roasted veggies, and gggggrrrraaaaavvvvvvyyyyyy! Nectar of the gods, culinary panacea, restorer of succulence, keeper of the peace, and defender of the realm of Thanksgiving with the family.

There is only one hitch in a wine lover’s buffet of Thanksgiving side beneficence - pairing wine with turkey is a snap (just follow the general rules for roast chicken), but what about the sides? What, besides marshmallows, goes with sweet potatoes? “(“Drowsy” uncle voice) What even is a brussel sprout, really?” Fear not, Thanksgiving drinker, The Thief is here to help! These are some of our favorite side dish pairings with wines that are also all perfect for that roasted bird centerpiece.

Anne-Sophie Dubois Fleurie Les Cocottes 2019

Anne-Sophie Dubois is one of our favorite producers in Beaujolais. Her bright, floral Fleurie, all clean lines and pillowy carbonic texture, with oodles of raspberry and strawberry, is perfect for the ubiquitous side of mashed sweet potatoes or roasted squash. Blend up some roasted squash with coconut milk and red curry paste for a delicious, spicy curried soup that makes a great starter.

Francois Chidaine Touraine Gamay 2019

Chidaine, one of the most inspiring farmers in all of France, produces biodynamic Chenin blanc, Sauvignon blanc, and this Gamay from his no-till, carbon-sequestering vineyards in the Loire. This Gamay is spicier and denser than Dubois’s, with darker fruit and a touch of leafiness that reminds me of a Cabernet Franc from the region. Sausage and Gamay is a classic pairing, so pour this when the sausage and sage stuffing makes it to your plate.

Domaine Sebastien David Hurluberlu Cabernet Franc 2019

Sebastien David’s funky, Coke bottle Cabernet Franc is perfect for anyone who enjoys stuffing version 2.0 - cornbread stuffing. The red and green capsicum notes of Loire Cabernet Franc pair beautifully with the southwest flavors of cornbread stuffing with roasted poblano chiles. The earthy spice and herbaceous tang will also elevate butter-roasted mushrooms with thyme and garlic.

Poderi Cellario E Rosso! NV

Barbera is incredibly versatile on the table, and this bright, natural wine comes in a one Liter bottle, so you’ll have plenty to go around. Barbera’s friendly fruitiness and acidity are perfect for difficult pairings like bitter vegetables. I like to brighten the umami-laden Thanksgiving table with a bright, punchy, raw Tuscan kale salad. Just dress thinly chiffonade-ed kale with lemon juice and olive oil, leave it to marinate and tenderize for a few minutes, then toss with sharp pecorino or parmesan. Serve with pine nuts if you like, or just a second glass of Poderi Cellario Barbera. Extra credit - this wine is perfect if you’re one of those folks who has abandoned turkey altogether in favor of a standing rib roast.

Weninger Blaufrankisch Kirchholz Alte Reben 2015

When in doubt, follow the number one rule of wine and food pairing - if it grows together, serve it together. This biodynamic Blaufrankisch (also known as Lemberger) from far eastern Austria is perfect with bacon-roasted brussels sprouts, roasted beets tossed with cumin seeds, and other eastern European flavors. It is dark and spicy, with cracked black pepper and blackberry coulis that make me think pork or game (maybe wild boar?), if you’re avoiding turkey.

Francois Labet Bourgogne Rouge Vieilles Vignes 2016

Labet’s old vine bottling is an absolute steal, with pretty red fruit and classic Burgundian polish framed by sappy whole cluster tannins and turned earth, like someone in a fancy ball gown or tuxedo who also has calluses on their hands and dirt under their fingernails. The slight stemminess, combined with Burgundy’s affinity for mushrooms, makes this wine ideal for classic green bean casserole. I usually like to make my own mushroom gravy, but I will never sneer at mushroom soup or mix.

As mentioned, all of these wines are awesome with simple salt and pepper roasted turkey (consider spatchcocking it to help the white meat and dark meat cook at the same rate), or deep-fried turkey, or smoked turkey, or flamethrower scorched goose, or confit-ed wild grouse, or whatever fowl you are planning to serve. If you are still thirsty when pie is served, feel free to switch to one of our sticky dessert wines. Port or Banyuls are perfect for pumpkin pie, while Tokaij, sweet German Riesling, or Sauternes are great with orchard fruit desserts like apple pie or Bosc pears poached in white wine. Eat well, drink well, and please be safe this Thanksgiving season. Cheers!

ROCKIN' REDS FOR THE TURKEY TABLE 6-PACK, SHOP HERE

Fleurie's Gracious Host: Jean-Louis Dutraive

FLEURIE JOIE DE VIVRE DUTRAIVE 3-PACK, SHOP HERE

We in the wine industry have a tendency to idolize reclusive winemakers, to lionize the hermit-artists who just want to be left alone with their barrels and bottles. Jacques Reynaud, the former owner of Chateau Rayas in Chateauneuf-du-Pape, was famous for hiding when journalists and importers would come calling, going so far as to crouch into a ditch to avoid an appointment with a famous wine writer. The cellars of Coche-Dury and Domaine de la Romanee-Conti (makers of arguably the greatest white and red Burgundies, respectively) are notoriously difficult to visit. The most famous hill in the Rhone was literally a medieval knight’s hermitage!

Jean-Louis Dutraive, on the other hand, is no shrinking violet. His domaine in the Beaujolais Cru of Fleurie has become a crossroads for visiting wine professionals, winemakers both local and imported and a rotating cast of interns from around the world. His devotion to casse-croute is famous (specially locally made sausages), and any visit to Dutraive’s cellar is bound to include a meal, along with enough Fleurie to float you to Lyon.

Dutraive’s family has been farming the Domaine de la Grand Cour since the early ’70s. The heart of their holding is the Clos de la Grand Cour, a walled vineyard whose vines are now more than 50 years old on average. Jean-Louis took control of the domaine in 1989, slowly fortifying his holdings to the current ~25-acre expanse. All of his estate vineyards have been farmed organically for decades (though they were only certified in 2009), and he incorporates herbal teas as well as plowing with donkeys to further lessen his environmental impact.

Domaine de la Grand Cour’s winemaking is similar to the famous Gang of Four. All of the grapes are hand-picked into small bins before they are refrigerated overnight. The cold grapes are loaded into small cement cuves the following day, covered with CO2, and left to carbonically macerate for 15-30 days. As with other natural Beaujolais producers, there is no addition of sulfur before or during fermentation, and the macerations are rarely touched at all, except for analysis. Dutraive describes his winemaking as “low intervention, high surveillance”, which is similar to other natural producers like Lapierre or Foillard.

Jean-Louis’s wines are as open and friendly as his cellar. Cool carbonic maceration leads to intensely aromatic wines with delicate, filigreed tannins that drink well on release, while also aging remarkably well. Fleurie is known as a lighter, more floral Cru than the more structured wines of Morgon or Moulin-a-Vent (some even believe, wrongly, that this florality is where the village got its name. It is actually named for a Roman general, Floriacum), and Dutraive’s wines take this luminosity to a different level. His Fleuries are often among the appellation’s lightest in color, but they are also some of the most intense, with flower-shop aromas of wet rose petal, violet, and agua de jamaica, and a palate that bursts with fresh red fruits like pomegranate, sour cherry, and wild strawberry. If I had one critique, it would be that they are almost too friendly, too easy to drink. Just what you would expect from one of the wine world’s most gracious hosts.

FLEURIE JOIE DE VIVRE DUTRAIVE 3-PACK, SHOP HERE

Lapierre: 100% Grape Juice

100% Grape Juice

“Our ideal is to make wine from 100% grape juice.” - Marcel Lapierre

BEAUJOLAIS GANG OF FOUR PACKAGE DEAL, SHOP HERE

It’s a simple idea: glossy, fragrant wines made from old, low-yielding, organically farmed Gamay vines. Unfined, unchaptalised, unfiltered, with only a sprinkling of sulphur at bottling, if at all. Wine produced solely from grape juice should not be a controversial idea. When you learn the full range of enological powders, potions, and poultices, though, you realize that we take for granted the industrial processes and additives that bring us the majority of the world’s wines.

The systemic use of chemical herbicides and pesticides in the vineyard and additives in the winery began after World War II and accelerated during the ’70s and ’80s. This is the wine world that Marcel Lapierre entered when he took over his familial domaine in the 1970’s. The recipe for Beaujolais was simple then: push yields as high as the Appellation allowed, pick before full ripeness to avoid inclement weather, chaptalise heavily, ferment quickly using selected yeasts, and shovel as much Nouveau into the market as it would take. Lapierre worked this way for several years, growing more and more frustrated with his results. It was not until 1981, when Marcel met Jules Chauvet, that Lapierre Morgon was truly born.

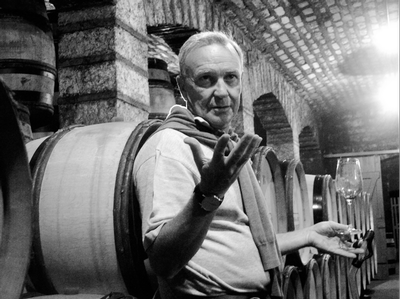

Look at the back of a wine label. There will be a warning about alcohol and sulfites, and very little else. Unlike other food products, wine labels are not required to list ingredients. Chauvet, a chemist, and brilliant taster, convinced Lapierre to set aside his herbicides, yeasts, and table sugar, relying instead on the plow and the microscope. This style of winemaking is sometimes called a la ancienne, or ‘the old way”, and it was said that Lapierre rediscovered the old taste of Morgon. His neighbors took note, and soon producers like Jean Foillard, Guy Breton, and Jean Paul Thévenet (sometimes known as the Gang of Four) began to work in a similar fashion. It was decades before Cru Beaujolais would receive international recognition, but the foundation was laid in Marcel Lapierre’s cellar. To this day, the domaine’s back labels still indicate whether the cuvee was sulfured (“S”) or unsulfured (the highly sought after, infrequently imported “N” bottles).

As I mentioned, it starts with intense, meticulously farmed grapes from some of Morgon’s finest climats (such as Cote du Py). Whole grape clusters are transported to the heavily-muraled winery, where they may chill overnight in a refrigerated truck. They’re then loaded into large wooden fermenters for a long, unsulfured carbonic maceration. Carbonic maceration is a complicated anaerobic enzymatic process; all you really need to know is that this is what gives Cru Beaujolais its beautiful aromatics and silky texture. After 2-4 weeks, the grape clusters are raked out and pressed, producing a low alcohol (~4%) juice called “paradis”. This juice is transferred to barrel or foudre, where it completes alcoholic and secondary fermentation under constant microscopic observation.

These days, it is Marcel Lapierre’s children forking grape clusters and running the microscope. Marcel passed away during the harvest of 2010. His children continue to produce Morgons in the house style that he debuted 40 years ago, and the Gang of Four continues to inspire natural winemakers the world over. Lapierre Morgon is a melange of bright berry intensity, allspice bite, and granitic nervosity, like skipping a wet stone across a raspberry juice pond in mid-fall; a true benchmark in the world of grape juice.

“Nobody’s wines taste like Marcel Lapierre’s. He is the source of a whole new school of winemaking, turning the hands of time back to wine the way Mother Nature envisioned it. Tasting it can change the way you taste wine.”

- Kermit Lynch, American importer for Marcel Lapierre and the Gang of Four